Since time immemorial, incense sticks have been in use. Here they are burning (for auspicious reasons) at the start of day in a mobile ‘phone shop in Bangalore … for me, this juxtaposition of ancient and modern encapsulates life in modern India.

Since time immemorial, incense sticks have been in use. Here they are burning (for auspicious reasons) at the start of day in a mobile ‘phone shop in Bangalore … for me, this juxtaposition of ancient and modern encapsulates life in modern India.

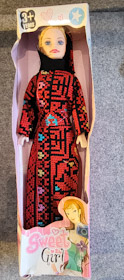

THERE IS A SUPERB exhibition at Cambridge’s Kettles Yard until the end of October 2023. The beautiful exhibits are mainly garments embroidered by Palestinian women before and after 1947. There are also a few other items including Palestinian propaganda posters depicting women wearing embroidered garments. The labels next to the exhibits are full of interesting information. Several of the topics particularly interested me.

Some of the garments were made using scraps of pre-used materials – for example bits of old clothes or even sacking and other packing materials. These old textiles were stitched together to create new clothes. This reminded me of a similar recycling of old materials which I saw at an exhibition of Japanese recycling at London’s Brunei Gallery.

I saw examples of Palestinian dresses which seemed very long. The length of these skirts was for a purpose. The cloth could be raised up to produce pocket like folds in which objects could be carried. These dresses were worn by Bedouins living in the Bethlehem and Jerusalem areas.

There was a widow’s dress. It was dark blue – the colour signifying grieving – and trimmed with red threads, which signified that the wearer was ready to be remarried.

One room was dedicated to embroidery and how the troubled situation in Palestine affected it. In refugee camps, some of the traditional materials were unavailable, and women had to embroider using whatever threads they could get hold of. There were several embroidered dresses adorned with decorations including the Palestinian flag and other patriotic motifs. These were displayed in the same room as the pro-Palestine propaganda posters that show women wearing embroidered garments.

I hope that what I have written gives you something of the flavour of this fascinating exhibition. Despite the intense reactions that discussing the plight of the Palestinians often arouses, the exhibition at Kettles Yard takes a reasonably balanced view of the situation. Its emphasis is on the skills of the Palestinian embroiderers rather than the politics of the part of the world where some of them still reside.

WHEN I WAS a child, I used to enjoy leafing through a book filled with black and white photographs of places in all the counties of England. One of them that stuck in my mind was of a wall covered with large horseshoes. It was only today (the 11th of August 2023) that I saw this wall in ‘real life’. It is in the great hall of Oakham Castle in England’s smallest county – Rutland. The hall, a fine example of Norman architecture, was built between about 1180 and 1190 for one of William the Conqueror’s grandsons – Walkelin de Ferrers. The name ‘Ferrers’ is related to the French word for iron and the English word ‘farrier’, who applies shoes to horse’s hooves.

The Ferrers family held Oakham for about 130 years. It might have been during that time, or certainly by the early 16th century that a curious tradition was established. It was decreed that every peer of the realm who visits Oakham for the first time must donate a horseshoe to the lord of the manor. That tradition is continued even today. Some 245 larger than life horseshoes have been donated to Oakham and many of them can be seen within the great hall. It is likely that others were donated, and subsequently lost. Most of the horseshoes on display bear the names of the donors and the date when they were donated – that is, the year the donor first visited Oakham.

Three of the horseshoes all bear the date 1921, which was when their donors (the future King Edward VIII, the future King George VI, and Princess Mary – daughter of King George V) all visited Rutland as part of a hunting party. Also in 1921, Oakham was visited by Frederick Rudolph Lambart, 10th Earl of Cavan. In 1917, he took command of the British forces in Italy. His horseshoe is mounted on a wooden board. It surrounds a real horseshoe, which had once been worn by an Austrian pony, which he captured after a raid on enemy trenches in Asiago. Another visitor to Oakham was William Edwardes, 3rd Baron of Kensington, after whom Edwardes Square (in Kensington) was named. He visited in 1855. One could continue, but I will not because the biographies of the illustrious donors are too numerous to describe in this short essay.

Another special feature of the great hall is that it is still a working Crown Court. It is used occasionally. Of all the Crown Courts in England, this has remained housed in its original building longer than any others in the country.

Apart from the fascinating great hall, the tiny town of Oakham has many other interesting things to see including a market cross, a fine museum, a gothic parish church, and Oakham School (founded 1584). However, the hall full of horseshoes is by far the most interesting thing to visit. I was pleased to see it even if so many decades have elapsed since I saw a photograph of it during my childhood.

Feed the cow

Pat her gently on the fore head

Surely you will be bless‘d

WHILE WANDERING THROUGH the large rambling bazaar in Mandvi, which is in the former Kingdom of Kutch (now part of Gujarat), we came across a workshop where bandhani textiles for clothing were being made.

Bandhani is a method of producing patterned dyed silks and cotton. Put simply, a piece of cloth, already dyed one colour or not at all, is prepared as follows. Parts of the cloth are gathered up to form tight bundles fastened by fine threads. The bundles, which look like small pimples are distributed to form patterns. The tied cloth is then dyed. The dye reaches all parts of the cloth except those enclosed in the tiny bundles. When the bundles are untied the patches of the cloth that had been shielded from the dye remain the original colour. This process can be repeated several times using different dyes to create an interesting pattern.

The shop the looked at, Khatri Ibrahim Siddik & Co, is the oldest bandhani workshop in Mandvi. It has been run by the same family for fifteen generations .

During our recent visit (January 2023), we have come across several businesses that have passed from generation to generation. In Bhuj, the Shivam Daining (sic) restaurant is run by chefs whose great grandfathers, grandfathers, and fathers, have all been cooks to the Maharaos of Kutch. Likewise, there is a bakery in Bhuj with an ancient wood fired stove. This business has passed through at least four generations. Nearby, there is a knife, scissors, and sword maker, who is the fourth or fifth generation of a family, which has been in this trade for over more than a century.

I am certain that there are plenty more examples of families in Kutch specialising in skills that have been passed from one generation to the next. I wonder whether these skills are in the genes, or simply taught by one generation to the next, and so on.

THERE IS A COPY of an icon, originally painted in Constantinople, in Truro Cathedral. This well-executed replica stands near the west end of the chancel. It depicts the Holy Child, Jesus, being held by the Virgin Mary. It exemplifies what we were told several years ago whilst being shown around a collection of icons in the Sicilian town of Piana degli Albanese, whose population is descended from Albanians who fled from the Ottomans in the late 15th century. These folk speak not only Italian but also a dialect of Albanian, known as Arberesh.

The icon in Truro shows the Virgin Mary dressed in dark blue and Jesus dressed in red. Our guide in Piana had shown us that in all the icons, the same thing can be seen. Conventionally, in Byzantine icons, Jesus is almost always dressed in red and the Virgin Mary in blue. The copy of the icon on display in Truro Cathedral is no exception to this tradition.

HAMPSTEAD GARDEN SUBURB (‘HGS’) in north London, where I spent my childhood and early adulthood, is a conservation area containing residential buildings designed in a wide variety of architectural styles. It first buildings were finished in about 1904/5. Despite this, many of the suburb’s houses and blocks of flats were designed to evoke traditional village architecture. Much of HGS contains buildings that do not reflect the modern trends being developed during the early 20th century, However, there are a few exceptions. These include some houses built in the ‘moderne’ form of the Art Deco style, which had its heyday between the two World Wars.

A few Art Deco houses can be found in Kingsley Close near the Market Place (see https://adam-yamey-writes.com/2022/02/07/art-deco-in-a-north-london-suburb/), and there is a larger number of them in the area through which the following roads run: Neville Drive, Spencer Drive, Carlyle Close, Holne Chase, Rowan Walk, and Lytton Close. The part of HGS in which these roads run was developed from about 1927 onwards, mainly between 1935 and 1938. So, it is unsurprising that examples of what was then fashionable in architecture can be found in this part of the suburb. According to an informative document (www.hgstrust.org/documents/area-13-holne-chase-norrice-lea.pdf) about this part of HGS:

“… A relatively restricted group of established architects undertook much development such as M. De Metz, G. B. Drury and F. Reekie, Welch, Cachemaille-Day and Lander, and J. Oliphant. H. Meckhonik was a developer/builder and architects in his office may have designed houses attributed to him.”

Most of the Art Deco houses on Spencer Drive and Carlyle Close leading off from it are unexceptional buildings, whose principal Art Deco features are the metal framed windows (made by the Crittall company) with some curved panes of glass. Fitted with any other design of windows, these houses would lose their Art Deco appearances. Number 1, Neville Drive displays more features of the style than the houses in Spencer Drive and Carlyle Close. There is, however, one house on Spencer Drive that is unmistakably ‘moderne’: it is number 28 built in 1934 without reference to tradition. It is an adventurous design compared with the other buildings in the street.

Numbers 13 and 24 Rowan Walk, a pair of almost identical buildings which stand on either side of the northern end of the street, where it meets Linden Lea, stand out from the crowd. They have flat roofs and ‘moderne’ style Crittall Windows. Built in the 1930s, they are cubic in form: unusual rather than elegant.

I have saved the best for last: Lytton Close. This short cul-de-sac is a wonderful ensemble of Art Deco houses with balconies that resemble the deck railings of oceanic liners, flat roofs that serve as sun decks, curved Crittall windows, and glazed towers housing staircases. Built in 1935, they were designed by CG Winburne. I have to admit that although I lived for almost three decades in HGS, and used to walk around it a great deal, somehow I missed seeing Lytton Close (until August 2022) and what is surely one of London’s finer examples of modern domestic architecture constructed between the two world wars. Although most of the Art Deco buildings in HGS are not as spectacular as edifices made in this style in Lytton Close and further afield in, say, Bombay, the employment of this distinctive style injects a little modernity in an area populated with 20th century buildings that attempt to create a village atmosphere typical of earlier times. The architects, who adopted backward-looking styles, did this to create the illusion that dwellers in the HGS would not be living on the doorstep of a big city but instead far away in a rural arcadia.

As we approach the end of the year, the pandemic rages on, the weather is appalling, and prospects for post-Brexit UK are not yet looking too bright. But all is not doom and gloom. On Christmas Eve, we went for a walk from Knightsbridge to St James Park. As we reached Hyde Park Corner and the Wellington Arch, an ever present reminder of the days when ‘England ruled the waves’ and a great deal more, we heard the sound of horse’s hooves behind us. We turned to look back at the arch and saw a line of mounted soldiers with shining helmets adorned with red tassels emerging from beneath the arch.as they have been doing several days a week for very many years, if not for several centuries. Seeing this age-old tradition being enacted in front of us reminded me that although much has been disrupted since the covid19 virus began ruling the waves, life goes on.

WILL BAXTER WAS a teacher at the University of Cape Town, whilst my late father was studying for a BComm degree before WW2. Will, recognising my father’s academic excellence, persuaded my father’s mother that she and her family would do well to subsidize my father continuing his studies in London. When he presented his case to Dad’s mother, my grandmother was at first surprised and said that my father’s siblings were even brighter than him. By all accounts, my father and his three siblings were well-endowed with brain power. My grandmother agreed, but before Dad was able to set off for London, there was another hurdle. Dad had become articled to an accountancy firm in Cape Town. Leaving this would have involved breaking a legal contract between him and the firm. Will spoke to the senior partners and managed to get Dad released from his contract. Then, the year before WW2 started, Dad sailed to England and enrolled for higher studies at the London School of Economics (‘LSE’). With the exception of a few of the war years and one year in Montreal (Canada), Dad spent the rest of his life in London, where I was born.

Will Baxter returned to the UK and taught at the LSE and became a firm family friend. My earliest reminiscences of him were at Christmas time. Until I was in my mid-teens, we used to visit Will and his wife at his home in the Ridgeway in Golders Green on Christmas morning. We used to have warm drinks in the living room in which there was always a large, decorated Christmas tree. Will always had wrapped presents ready for my sister and me, always books. I cannot remember which books I was given, but I do recall that every year my sister always received a beautiful hardback edition of one of the classic British novels by authors such as Jane Austen or one of the Bronte sisters.

The Baxters’ front garden had a gate supported by brick pillars. When I was about 3 or 4, we visited the Baxters one morning (not on Christmas Day), soon after the mortar between the bricks had been renewed. It was still wet, and Will inscribed a small ‘A’ in the mortar to record how high I was on that day. Year after year when we visited the Baxters, the letter was there in the set mortar, but my height had increased considerably. After many years, several decades, it disappeared after Will and his second wife, his first having died many years previously, had had the pillars refurbished.

Always after our Christmas morning visit to the Baxters, we walked or drove over to my mother’s sisters’s home, where we ate a festive lunch, often featuring roast goose. In addition to my close family and my aunts, other people attended this party. These included my aunt’s in-laws, various people we knew who had no close family in London, and my uncle Felix, my mother’s brother.

Felix, more than many of the other adults, truly enjoyed our Christmas lunches. He entertained us kids, my two cousins, my sister, and me, by tales of ‘Turkey Lurky’, ‘Goosey Lucy’, ‘Ducky Lucky’, and similarly named fowl. However, as we grew older, he failed to realise that we had become a little more sophisticated and blasé to enjoy this type of entertainment. At the end of the main course, he used to interrupt the adults’ conversation by standing up, thumping the table, and singing a song about bringing us some ‘figgy pudding’. I noticed that it always annoyed the adults and especially my aunt who was already stressed enough already, having produced a magnificent meal for 15 or more people.

After lunch, we retired to the living room to open presents, and always enjoyed. Felix always felt it necessary to entertain us, his nieces, and nephews, after lunch. To this end, he brought along packets of coloured inflatable balloons. He inflated them and asked one of us to hold them at their necks whilst he knotted them. Next, he twisted and tied the balloons together to make sculptures of animals. I hated these balloons because I could not tolerate the goose-pimples that the squeaking of the balloons set off in me, and still do today. One of my cousins did not enjoy this balloon experience because of the risk that a balloon might pop noisily. It is probably to our credit that none of us, his nephews, ever told him how much we disliked the balloons that Felix always brought with him.

Christmas lunches at my aunt’s house ceased many years ago. For many years, I spent Christmas enjoyably with the family of my PhD supervisor and his wife, with whom I became close friends. Then later, we often spent Christmas in India, in Bangalore where my in-laws live. This year, we had planned to do the same, but, in common with everyone else, this plan had to be abandoned for reasons that need no explanation.

I have celebrated Christmas Day at my aunt’s house, in Paris, in Méribel-les-Allues, in Manhattan, in Bangalore, in Stoke Poges, in Belgrade, in Wrocław, on a ‘plane to Sri Lanka, in Cornwall, and in Cochin, but until this year, never at home. So, this year is a first for me: Christmas at home.