OUR FIRST EXHIBITION IN FORT KOCHI (KERALA) 2026

WE HAVE COME to Fort Kochi (Fort Cochin) in the south of India to view art in the town’s Kochi Muziris Biennale. This art show is housed in a wide variety of places in Fort Kochi and its environs. There is a main exhibition area and numerous peripheral venues. The first show we visited in housed in Burgher Street, almost opposite the popular Kashi Art café. At this location, Gallerie Splash from New Delhi was hosting images created by Naina Dalal, who was born at Vadodara, Gujarat, in 1935.

Ms Dalal studied art first at MS University in Vadodara, then at London’s Regent Street Polytechnic, and later at Pratt Graphic Center in New York City. She was one of the first Indian women artists to explore the nude artistically.

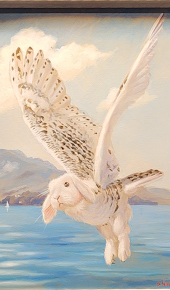

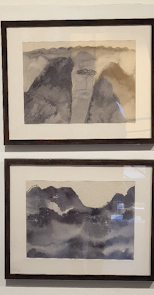

The exhibition in Fort Kochi, “An Empathetic Eye”, includes watercolours, oil paintings, and various types of print including collographs. According to Wikipedia:

“Collagraphy (sometimes spelled collography) is a printmaking process in which materials are glued or sealed to a rigid substrate (such as paperboard or wood) to create a plate. Once inked, the plate becomes a tool for imprinting the design onto paper or another medium. The resulting print is termed a collagraph.“

The works on display in the exhibition were attractive and visually intriguing. Dalal provides fine examples of Indian Modernism that demonstrate her independence from the previously powerful influence of Western European artistic styles on Indian modern art.

Seeing this exhibition made a great start to our exploration of what is on offer during the Biennale that runs until the end of March 2026.