I WAS STAYING IN BELGRADE with my friends Peter and his wife. Peter said to me that because it was just over the border from (the former) Yugoslavia and neither of us had been there before, we should make a short trip to Hungary. That way, we could ‘tick off’ another country as having been visited. I agreed to accompany him. This was in 1981 when Hungary was still in the Soviet bloc.

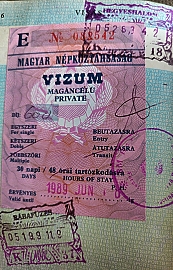

British people required a visa to enter Communist Hungary. The Hungarian embassy in Belgrade was in Krunska, a leafy street near the Hotel Slavija. I entered and filled in a form. One of the questions on it related to the colour of an applicant’s car. It gave several options like ‘red’, ‘blue, or ‘green’, and one translated from the Hungarian as ‘drab’. I suppose that ‘drab’ was a mistranslation of the Hungarian word for ‘grey’ (the Hungarian for ‘grey’ is ‘szürke’ and for ‘drab’ is ‘sárgásszürke’). After filling the form, I walked to a counter by a small window in the wall. It was covered by an opaque green cloth curtain. I waited. After a few moments, the curtain was pulled open sharply by a lady behind it and the counter. I handed her my passport and the application form. My passport was full of bits of paper that I wanted to preserve safely. The lady plucked these out of the passport and handed them to me, saying:

“This I do not need.”

I picked up my passport with its new multi-coloured Hungarian visa stamp a couple of days later.

Peter and I boarded an overnight train from Belgrade to Budapest. Very soon, Peter fell asleep. After passing the station of Subotica in northern Serbia (Vojvodina), we reached the Hungarian border station at Kelebia. The train halted at the floodlit station for a long time. Apart from a few men in uniform, the platforms were eerily empty. Hungarian border guards entered the train. They carried satchels with shoulder straps. Each satchel was fitted with a hinged wooden lid that served as a small desk. Peter was sleeping deeply when two border officials entered our compartment. It was with great difficulty that the three of us, the two officials and I, managed to get him to open his eyes. Once he was awake, the guards took our passports. They looked at our passport photographs and then at our faces, and then back at the photos, then at our faces, and so on. This procedure was repeated several times until they were satisfied that our ‘mugshots’ were true likenesses of Peter and me. Then, they placed each passport on to the little desks attached to their satchels and pounded them with rubber stamps.

Some years later, the late Arpad Szabo, a philosopher in Budapest and a good friend, told me what he did when he was travelling out of East Germany (the former DDR) by train. The border guards in that country were particularly tough and very thorough. They entered his compartment and began prodding and opening the passengers’ baggage. When they approached his bag, he told them:

“Be careful with my luggage: I am smuggling an East German out of your country.”

The guards failed to appreciate the humour.

We arrived in Budapest Keleti Station early in the morning with no idea where we were going to stay. Someone directed us to a small window in a booth in the station. It was an official agency for arranging accommodation in people’s homes. We registered and were handed a scrap of paper with the address of our hosts. Without knowing the layout of the city, we hailed a taxi, which drove us across one of the Danube bridges to Obuda, a suburb north of Buda. Our accommodation was with a couple, who lived in a flat high up in a modern tower block. They were friendly but spoke no English. Somehow, I managed to communicate with them my interest in folk music. They recommended a singer called Katalin Madarász and told me that there were good record shops in Vaci Utca (Vaci Street), a shopping street in central Pest.

We made our way to Vaci Utca, where we found the Anna Café. This eatery served the most delicious cakes and savoury snacks in the form of open sandwiches. We found the record shops that we had been told about and that afternoon I bought the first of many Hungarian folk and classical LPs that are still in my enormous collection. I ate a toasted sandwich in a Café named Martini. It was there that I was able to add the words ‘meleg szendvics’ (hot sandwich) to my minute knowledge of Hungarian, a language outside the Indo-European language family.

I fell in love with Budapest, with the unfamiliar (to me) vocabulary of the Hungarian language, the food, and the friendly people we met. Peter and I explored many things in the city including a visit to the Young Pioneers’ Railway that ran in the Buda Hills. This was run and operated smoothly by youngsters, mostly teenagers, dressed in uniform. We visited Szentendre, a village north of Obuda, the Hampstead of Budapest. Not only is this place picturesque, but also it has a significant community of people with Serbian ancestry as well as a Serbian Orthodox church.

One evening, Peter wanted to visit a night club. In the early 1980s, Budapest seemed devoid of life after dark, but we found that the Hotel Astoria boasted a night club. This was entered through a discreet, almost hidden, street entrance and then up a staircase. We entered a darkened room full of people seated at tables. Soon, the cabaret, such as it was, began. The highlight of the rather unadventurous show was a magician performing tricks. The audience was subdued but showed its appreciation by genteel clapping. The people seated around us did not look as if they were used to visiting night clubs; they looked dowdy and provincial. I am quite sure that what was on offer at the Astoria was not what Peter was hoping for.

I do not know whether Peter ever visited Budapest again, but I did often. My appetite for Hungary was truly whetted by my first brief visit. I made another trip the following year, but not before doing some careful ‘contact tracing’ as they say in the current pandemic crisis. I wanted to meet Hungarians in their homes. One of my many contacts was supplied by my PhD supervisor’s wife, Margaret.

Margaret, gave me the contact details of Dora Sos. Dora was trained as a chemist in Hungary. Just before WW2 started, her company sent her to the UK on a business trip. When the War broke out, she was stuck in Britain and detained as an ‘enemy alien’. Soon, she was released from internment because she was not regarded as being a threat to the security of the UK. She was sent to work in a chemical laboratory in the Slough Trading Estate, just west of London. There, she met and assisted Margaret in her work connected with extracting valuable elements from household and other metal goods donated for the war effort. Dora and Margaret became close friends. During her stay in Britain, Dora was given a British passport.

After the war, Dora returned to Budapest and began working in a laboratory there. Every now and then, the British embassy invited her and other holders of British passports to parties. One evening, she arrived at the embassy, but the Hungarian guards at its door prevented her from entering. She was arrested and her British passport confiscated. She was told never to visit the embassy again. This would have been during the harsh times, when Stalin was still alive and before the failed 1956 Hungarian Uprising.

Working in the laboratory soon became difficult and unpleasant. Every night, everything, all notebooks and other paperwork, had to be locked up. An atmosphere of secrecy and suspicion reigned. As Dora had lived in the West, she was regarded as being unreliable by the state. She left and became an interpreter: she was fluent in Hungarian, German, and English.

Some years later, restrictions eased a little in Hungary. Dora was permitted to visit Holland, which she did using her Hungarian passport. She made her way straight to the British Embassy at The Hague and told them about her British passport. After checking her story, the ambassador issued a replacement. He told Dora that in the future when she wanted to travel, she should travel somewhere with her Hungarian passport and then she could pick up her British passport at the British embassy at that place. And, when she was about to return to Hungary, she was to hand it into the nearest British embassy at the end of her trip. This worked well for her. A British passport was subject to far fewer visa requirements and travel restrictions than a Hungarian one.

By the time I first met Dora in her flat in Buda, she had stopped travelling abroad. In her seventies, she was still busy working as an interpreter. Because young Hungarians had to study Russian as a foreign language at school, few learnt German or English. This meant she was in high demand. At international technical conferences, she told me, she was able to make simultaneous translations for people speaking in German to those who only understood English and vice versa. It is not a common skill to be a three-way simultaneous translator.

Every time I visited Budapest, I used to spend time with Dora, usually in her flat. A chain smoker, she used to have frequent bouts of uncontrollable coughing. She was a good cook. Her speciality was chicken paprika, which she served with home-made pasta, which she extruded through a perforated metal disc straight into a pot of boiling water. I used to write to her before I arrived in Hungary, asking if there was anything she wanted from the West. Invariably, she asked for the latest editions of technical dictionaries, which she needed for her translation work. She did not ask for works of literature forbidden in Hungary, like the works of Solzhenitsyn. She enjoyed trying to smuggle those illicit books into her country after her occasional trips abroad. She told me that whenever she returned to Hungary, the customs officials would ask her if she was carrying any ‘Solzhi’ in her baggage.

While writing this, I remembered a joke I was told in Hungary. Two policeman’s wives were discussing the flats where they lived. One said boastingly:

“We’ve got Persian carpets on our floors.”

The other said:

“We’ve got Rembrandts on our walls.”

To which the first replied:

“Gosh how awful. How do you kill them?”

Enough of that. There was little for the average Hungarian to laugh about living in Communist Hungary. I recall seeing a shop where foreign goods could be obtained with hard currency (US Dollars, UK Pounds, Deutschmarks, Swiss Francs, etc.). Crowds of Hungarians pressed their noses towards the shop’s windows, staring at things that they might never afford. These goods, which were otherwise unobtainable in Hungary, included tins of Coca Cola, imported alcohol, western cigarettes, and electronic equipment that was no longer the latest in the world outside the ‘Iron Curtain’.

For several years after the ending of Communist regimes in Eastern and Central Europe, I did not return to Hungary. In the late 1990s, after our daughter was born, we drove to Hungary and stayed with some young friends in Budapest. Under Communism, Pest, which to some extent resembles 19th century Paris, lacked the ‘buzz’ of a city like Paris or London. After the end of Soviet control of Hungary, Budapest sprung to life as if it had come out of a coma or recovered from a general anaesthetic.

I wanted to introduce my wife to Dora. I tried ringing the number I had for her a few times, but there was never an answer. So, one morning we took a tram to the place where Dora had her flat. We entered the building and used the ancient lift to reach Dora’s floor. Her front door opened onto a gallery overlooking an inner courtyard where rugs were hung on wooden stands and beaten by their owners to rid them of dust. Dora’s name was no longer on the small plate next to the doorbell. I rang the bell. Nobody answered it. I never saw or heard from or of Dora again. Maybe, her chain smoking had finally got the better of her.

As for Peter, whose suggestion in Belgrade led to my love affair with Hungary, I lost contact with him for many years. About two years ago, we re-established contact via Facebook. Last year, after he and I had returned from our separate trips to India, we arranged to meet up again face to face. I was really looking forward to seeing this highly witty and intelligent friend of ours again. A few weeks before the rendezvous, he sent me an email telling me that he was unwell and that we would need to delay our meeting until he recovered. Sadly, he never did.

Picture shows Peter seated in the Young Pioneer’s Train at Buda