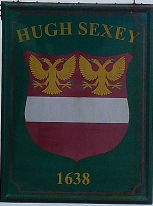

THE RIVER BRUE flows through the Somerset town of Bruton. In the Domesday Book (1086), its name was recorded as ‘Briuuetone’, which is derived from Old English words meaning ‘vigorously flowing river’. In brief, this small town is picturesque and filled with buildings of historical interest: a church; several long-established schools; municipal edifices; an alms-house; shops; and residences. On a recent visit, we drove past a Tudor building that was adorned with a crest labelled “Hugh Sexey” and the date “1638”. At first, I thought it was a sort of joke, rather like ‘Sexy Fish’, the name of a restaurant in London’s Berkeley Square. I walked back to the building after parking the car.

I looked at the sign, and my curiosity was immediately aroused. The crest bears a pair of eagles with two heads each, double-headed eagles (‘DHE’). Now, as some of my readers might already know, the DHE is a symbol that has fascinated me for a long time. This bird with two heads has been used as an emblem by the Seljuk Turks, the Byzantine and Holy Roman Empires, Russia (before and after Communism), the Indian state of Karnataka, Serbia, Montenegro, Albania, and some people in pre-Columbian America, to name but a few. In the UK, several families employ this creature on their coats-of-arms. These include the Godolphin, the Killigrew, and the Hoare families, to name but a few. Each of these three families has connections with the county Cornwall, which, through Richard, Earl of Cornwall (1209-1272) and King of the Germans, had a strong connection with the Holy Roman Empire, whose symbol was the DHE. Until I arrived outside the building in Bruton, Sexey’s Hospital, I had no idea about the existence of the Sexey family nor its association with the DHE.

Sir Hugh Sexey (c1540 or 1556-1619) was born near Bruton. He became royal auditor of the Exchequer to Queen Elizabeth I and later King James I, and amassed a great fortune. After his death, much of his wealth was used for charitable purposes in and around Bruton. Two institutions that resulted from his money and still exist today are Sexey’s Hospital, outside of which I first spotted the crest with two DHEs and Sexey’s School (www.sexeys.somerset.sch.uk/about-us/the-sexeys-story/). The school, which is now housed in premises separate from the hospital (now an old age home), was first housed in the same premises as the hospital.

According to the school’s website:

“…a two headed spread eagle is taken from the seal used by Hugh Sexey later in his life which can be seen on his memorial on Sexey’s Hospital …”

The article then considers the DHE (‘spread eagle’) as follows:

“Traditionally the spread eagle was considered a symbol of perspicacity, courage, strength and even immortality in heraldry. Prior to notions of medieval heraldry, in Ancient Rome the symbol became synonymous with power and strength after being introduced as the heraldic animal by Consul Gaius Marius in 102BC (subsequently being used as the symbol of the Legion), whilst it has been used widely in mythology and ancient religion. In Greek civilisation it was linked to the God Zeus, by the Romans with Jupiter and by Germanic tribes with Odin. In Judeo-Christian scripture Isa (40:31) used it to symbolise those who hope in God and it is widely used in Christian art to symbolise St John the Evangelist. An heraldic eagle with its wings spread also denotes that its bearer is considered a protector of others. Sexey’s seal and crest may have included the spread eagle to symbolise the family’s Germanic heritage.”

Some of this is in accordance with what I have read before, but I need to cross-check much of the rest of it, especially the Greek and Roman aspects. The final sentence relating to Germanic heritage seems quite sound, as the DHE was an important symbol in the Holy Roman Empire.

There is a sculpted stone bust of Sir Hugh Sexey in the courtyard of his hospital (really, almshouses), which was built in the 1630s. This portrait was put in its position in the 17th century long after his death. Above the bust, there is a carved stone crest bearing two DHEs, which was created by William Stanton (1639-1705) from London. According to the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (‘DNB’):

“ Later in the seventeenth century a stone bust of Sexey, together with a coat of arms (that of the Saxey family of Bristol, with which he had no known connection), was placed over the entrance hall…”

The plot thickens as I now wonder whether the DHEs are related to the Sexey family or that of the above-mentioned Saxey family. A quick search of the Internet for the coats-of-arms of both the Sexey and the Saxey families revealed no DHEs except on crests relating to Bruton’s two Sexey foundations.

One family that was involved in the history of Bruton and whose crest bears the DHE is Hoare. They took over the ownership of the manor from the Berkely family in 1776. This is long after Hugh Sexey died and is therefore unlikely to be the reason that William Stanton included the DHEs on the crest above Sir Hugh’s bust. So, as yet, I cannot discover the history of the DHEs that appear all over Sir Hugh’s hospital and neither can I relate them to any other British family that uses this heraldic symbol. But none of this should mar your enjoyment of the charming town of Bruton.