Not long ago, I wrote about Warren Street, which played a significant role during part of my life. Now, let’s move a little further south to a street, which is overshadowed by the Post Office Tower and contains many memories for me.

London’s Charlotte Street runs between Rathbone Place in the south and Maple Street in the north. It is just over half a kilometre in length. Laid out in 1763, it was named after Queen Charlotte, who married King George III. I began to get to know the street just under 200 years later.

My earliest recollections of Charlotte Street were regular visits in the early 1960s to the Hellenic Stores on the west side of the street south of Goodge Street. My mother bought olives and other Mediterranean products at this store and another Greek shop in nearby Goodge Street. The latter was smaller than the Hellenic Stores, and a little less honest. When something needed weighing in the Goodge Street shop, the shopkeeper would throw it on the scales. The weighing machine’s needle would flash across the dial, and before one had time to think, a price was given. Neither of these purveyors of Greek produce exist anymore.

Site of Schmidt’s, now rebuilt

During the twelve years (1970-82) that I studied at University College London (‘UCL’), I used to visit Charlotte Street often. As a student, I was always keen to find somewhere to eat cheaply. Schmidt’s on Charlotte Street was one such place. This was a German restaurant. Its dining area was on the first floor. Most of the waiters were pasty-faced gentlemen, who added to the gloomy atmosphere of the place. The ground floor served as a delicatessen. It contained a counter where boiled Frankfurter sausages were served with mustard and slices of delicious greyish German bread. They were very cheap and extremely delicious. A female cashier sat in a booth in the middle of the room. Whenever I saw her, she had a blackish facial hair where men grow moustaches. My father, who was in London during the 2nd World War, told me that during the conflict, the owners of Schmidt’s posted labels on their windows, which read: We are British, NOT German.”

There have always been plenty of eateries on Charlotte Street. L’Etoile, which I never entered because it was beyond my budget, was a long-established restaurant on Charlotte Street. It had a Parisian look about it, but like Schmidt’s, it has disappeared. Near to the posh L’Etoile, there was a Greek ‘taverna’ called Anemos. I never visited it, but plenty of my fellow students did. One did not visit Anemos for its food, but for its riotous atmosphere, which included music, dancing and the trational Greek practice of plate breaking. Venus was another Greek place that has long since disappeared. I was taken there several times by an uncle, who worked nearby and regarded it as his favourite Greek restaurant.

Just north of Goodge Street, there is another long-standing, and still existing, restaurant. This is the Pescatori, an Italian place specialising in fish dishes. It was one of my parents’ favourite restaurants in London. Back in the 1960s, there used to be a life-size boat suspended from the ceilings above the tables. I believe that my father was being serious when he said that he preferred not to sit beneath the boat, in case it fell.

There was another fish restaurant in Tottenham Street that leads east of Charlotte Street. Pescatori was at the high end of the scale of elegance, and Gigs was at the lower end. Gigs was very popular with students from UCL and workers in the neighbourhood. It was divided into two sections: take-away and sit-down. At lunchtimes, there was always a long queue at the take-away counter. Two gentlemen, oozing with sweat, took the orders for fish and chips and also for the delicious lamb shish kebabs they prepared while you waited. In between taking the cash and wrapping the fish and chips, they threaded lumps of lamb onto skewers, and grilled them. The kebabs were served with salad in a warm pita bread. As the saying goes, they were ‘to die for’. Despite the rather haphazard-looking hygiene, I know no one, who died from these mouth-watering bundles of meat and salad.

Gigs closed many years ago. Then a few years ago, the premises were modernised, and Gigs was brought back to life by some relatives of the original owners. What used to be the take-away section is now an attractive restaurant, and what used to be the sit-down area is now the take-away area. The updated Gigs is both hygienic in appearance and looks as if it is designed to attract a more sophisticated clientele than its ancestor.

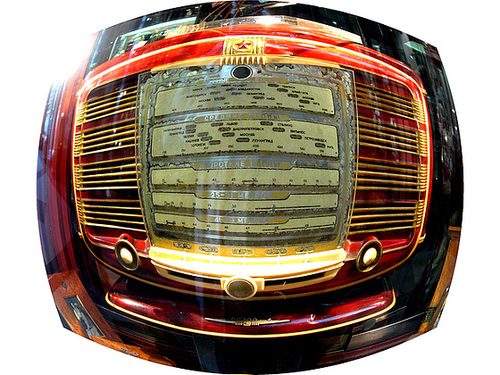

My father was a professor at the London School of Economics (‘LSE’) for most of his working life. The LSE has a hall of residence for students, Carr-Saunders Hall, a non-descript 1960s building on Charlotte Street. When it opened in 1964, my father’s colleague Kurt Klappholz was its first warden. Kurt, whom I knew well as a family friend, was a Polish Jewish Holocaust survivor. Later, another of my father’s colleagues was a warden there many years ago. Once, he invited me to his flat. This academic possessed the most wonderful sounding HiFi equipment that I had ever heard. The warden, who owned it, was rather over-built. He told me that he preferred listening to music sitting in a comfortable armchair in front of his HiFi, than trying to squeeze into uncomfortably narrow chairs in concert halls.

The building that used to house Cottrells

When I became a dental student, I became aware of Cottrells in Charlotte Street. This was near the Rathbone Place end of the street. It was the showroom for a major supplier of dental equipment. Housed in an elegant Victorian building, which still exists (it now contains a restaurant), the firm supplied everything from dental examination mirrors to entire dental operating units (chair plus attachments fordrills etc.) The technician responsible for teaching me how to cast gold crowns (caps) told me to visit Cottrells, not to look at the equipment, but, instead, the pictures hanging on the walls of the showroom. The walls were hung with a large collection of paintings by William Russell Flint (1880-1969). He specialised in depicting women. Well-painted, and quite artistic, the paintings on the walls of the dental showroom and of its main staircase fell very definitely into the category of extremely light porn.

One of the longer established shops in Rathbone Place: Mairants

Rathbone Place, a short street which connects the southern end of Charlotte Street contained a large postal sorting office. Quite late on in life, one of my uncles, a bachelor now sadly no longer living, got a job there as a postman. He often used to tell me about his experiences as a medical orderly in the South African Army in the North African desert during the 2nd World War. He spoke of them fondly, regarding the great camaraderie he experienced amongst his fellow serving men. I often felt that this was one the more enjoyable times in his long and varied life. When he joined the postal team at Rathbone Place in his fifties, he spoke of this in the same appreciative terms. He liked being part of a working team. Now, not only has my uncle gone, but also the sorting office no longer exists.

Charlotte street and its surroundings lie in the shadow of the Post Office Tower, which was ready for use in 1964. Until 1980, it was the tallest building in London. When it opened it had a revolving restaurant high above the ground. I never ate there, but did manage to visit the viewing platform just beneath it. When I looked up from this platform, I could watch the concrete base of the restaurant rotating slowly. A terrorist attack in 1971 put an end to the public being allowed to visit the viewing platform or any other part of the tower.

I still wander along Charlotte Street occasionally. Although it is still extremely vibrant, it evokes many memories of times long past.