AT A REUNION LUNCH held for students who (like me) had attended Highgate School in north London during the 1960s, the Headmaster, Mr Petitt, gave a speech. He said that we, the former students, had reached the age when the ‘nostalgia gene’ kicks in. In my case it has kicked with a vengeance. When I lived near Golders Green, which is not far from Highgate, I would never have believed that one day I would write nostalgically about this, let us be honest, fairly unexciting suburb in northwest London, but here I am at the keyboard doing just that. Squeezing some oranges to produce juice to flavour a dish containing red cabbage triggered one of my earliest memories, that of walking with my parents to the church hall next to St Albans Church in Golders Green to collect bottles of orange juice.

The juice collected from the church hall was quite delicious and richly flavoured. It was contained in large glass medicine bottles with cork stoppers. The juice was supplied free of charge by the state during the 1950s. It was first supplied gratis by the state in 1941 and distributed to reduce the risk of vitamin C deficiency amongst young British children. In 1951, just before I was born, the Conservative Party won a General Election. Soon afterwards, the government restricted the supply of free orange juice to children under two years. My sibling was born in 1956, four years after me. Therefore, I must have been well under six years old when we made these trips to the church hall in Golders Green. Thinking about this juice led me to recall other aspects of Golders Green as it was during my early childhood.

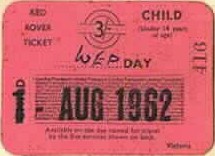

St Albans church hall in Golders Green

One dimly recalled early memory of Golders Green is of a delicatessen near the corner of Golders Green Road and Golders Green Crescent. The place was called Apenrodt’s. I remember this shop had a large wooden barrel that contained pickled gherkins submerged in a liquid. This was not a surprising thing to see in a suburb with a large Jewish population, many of eastern European heritage in my early years. My father enjoyed pickled gherkins. I developed a taste for them in my twenties, as I did for smoked salmon. In my childhood, smoked salmon was relatively more expensive than it is today. My parents regarded it as a treat. I remember them buying it at the aptly named Cohen’s Smoked Salmon, which, like Apenrodt’s, was a Jewish delicatessen.

Two shops in Golders Green particularly intrigued me when I was a little boy. One was an old-fashioned shop, Franks. It sold various clothing items, much of it was hosiery and lingerie. It was not the garments that interested me but the pneumatic system that was used to send money and receipts from the shop floor to an office somewhere else in the shop. Money, bills, and receipts were placed in cylindrical capsules that were placed in tubes along which air was pumped to propel them from one part of the shop to another.

The other establishment was Importers, a coffee retailer with a café behind it. The front windows contained cylindrical coffee roasters, which could be seen from the street. The cylinders were made with fine metal meshwork. Filled with coffee beans, they rotated slowly above gas burners. The air inside the shop was filled with a wonderful aroma that must have helped sell the coffee beans and powders stocked on the shelves of the shop and in the sacks on the floor. We used to pass this shop often, but rarely entered it because my mother preferred to buy coffee at the Algerian Coffee Store, which still exists in Old Compton Street in Soho. Despite this, I always stopped to watch the roasters rotating and savour the odour of the coffee whenever I passed that shop.

During the last three months of 1963, we lived in Chicago, Illinois. There, we experienced and enjoyed self-service supermarkets for the first time. So, I was excited when the first supermarket opened in Golders Green soon after we arrived back from the USA. I cannot recall the supermarket’s original name, but soon it was called Mac Market, when it was taken over by the Mac Fisheries Company. Prior to taking over the new supermarket, the company had run two grocery shops near to Golders Green station. These were stores where one queued up to be served by shopkeepers standing behind counters laden with food items. If you wanted a product, butter for example, the assistant cut the amount you required, weighed it, and wrapped it up.

The supermarket occupied a plot on the corner of Golders Green Road and a small service road called Broadwalk Lane on which there used to be a small pet shop. Years later, the building that housed Mac Market was occupied by a newer supermarket that stocked many Kosher and Israeli products. Currently, a branch of Tescos occupies the site of Golders Green’s first ever supermarket. Another supermarket built far later, a branch of Sainsburys, occupies the site of the Ionic, one of Golders Green’s two former cinemas. The other cinema, long since demolished, was the ABC that stood on Golders Green Road northwest of the main shopping area at the end of Ambrose Avenue. A care home now stands in its place. Although another of the area’s entertainment centres still stands, the huge Hippodrome Theatre, where as a child I enjoyed the annual pantomime and adults enjoyed pre-West End runs of new plays, this now houses the Hussainiyat Al-Rasool Al-Adham community centre, a religious organisation.

The supermarket was close to the bridge that carries the Northern Line of the Underground over Golders Green Road. We used to visit a small shop that nestled close to the southwest corner of the bridge. This was Beecholme’s Bakery, which was run by Harry Steigman and his family, who were related to my aunt’s husband. We visited the shop not to buy baked goods, but to greet these relatives of my father’s sister. She lived in South Africa, which felt very distant at a time when international telephone calls were costly, and the means of electronic communication that are now in common use were probably unimaginable even in the minds of science fiction writers.

What I did not know at the time was that one member of the Steigman family, Natty, the youngest of four brothers who helped their parents run the forerunner of Beecholme Bakeries, had volunteered to fight against Franco in the Spanish Civil War. Tragically, he was killed at the battle of Jarama (in February 1937) only two weeks after his arrival in Spain.

Crossing the main road from Beecholme’s and walking under the bridge, one reaches Golders Green Public Library. During my childhood, I loved this place. Until a certain age, maybe 12, I was confined to using the well-stocked Children’s Library. When I passed that age, I could borrow books from the much larger, and far more interesting Adults Library. One bookshelf of this section of the library contained books about the sad story of the Jewish people during period of the twentieth century when their persecution and destruction was being carried out to fulfil the evil plans of Adolf Hitler and his sympathisers. Reading books about this terrible period catalysed my interest in twentieth century history and what led up to it. When I was at school in the 1960s, every school year our history syllabuses led us from the arrival of Julius Caesar in Britain to just before the start of WW1, never beyond it. And, the emphasis was not on what happened and why, but on the dates of events. These books in the library opened my eyes to the history of a period that I found far more interesting than what we were expected to learn to pass examinations. Since those days exploring the shelves of Golders Green Library, my interest in history has gradually expanded from the twentieth century back to far earlier times.

The library was next to a branch of Woolworths. This old-fashioned store, a magnificent emporium, stocked everything from plant bulbs to lightbulbs, from liquorice to lawnmowers. Its ceiling was decorated with an elaborate stuccoed pattern. Although illuminated with electric lamps, some of the shop’s old-fashioned gas lamps still hung from the ceiling. They had little chains dangling from them to regulate the gas flow. Shoppers were assisted by salespersons. It was not a self-service store. Oddly, I have no memory of the shop after its modernisation in 1971.

Although the shops I remember from my childhood have disappeared, Golders Green Road’s buildings look much as they did when I lived near there, and the pavements are just as busy as they were in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

All the shops I have described have been replaced by others, reflecting the passing of time and the changes in the ethnic mix of the population living in the area. There is still a strong Jewish presence in Golders Green, albeit now biased towards the ultra-orthodox communities. To this has been added people from a diverse range of backgrounds. When I was a child, the idea of eating Japanese, Korean, Turkish, or even, surprisingly, Israeli foods would have been unthinkable in Golders Green Road.

St Albans Church, designed by the architect Sir Giles Gilbert Scott and built in 1933, remains unchanged. Neighbouring St Albans, the church hall, where we used to walk to collect the orange juice, also looks as I remember it so many decades ago.

Today, the shops that we visited when I was a child and collecting orange juice in corked glass bottles are merely memories of a childhood long since passed. As I type the final words of this piece, another memory of the church hall springs to mind. Between the ages of four and eight, I attended Golders Hill School on Finchley Road. Once, we, the school children, performed a play for our parents. We acted it on the small stage in the church hall. I had a minor role as a magician. The costume I wore included my beige dressing gown onto which my mother had embroidered different coloured cloth patches. They were cut to look like stars. For a long time after that show, I treasured the dressing gown as it held memories of an evening I had enjoyed greatly. I outgrew the dressing gown, but memory of it still lingers in the folds of my brain. And, yes, Mr Petitt was right, my ‘nostalgia gene’, clearly a dominant version of it, has become most powerfully active.