Surely it’s not

A drink from Scandinavia

No, someone can’t spell

IN SHEPHERDS BUSH Market, I noticed a shop sign written in Arabic, Ethiopian and Latin scripts. The Latin script read as follows:

“Afrcan custmory grments shop”.

Was this bad spelling of English words or maybe something else? It might have been the latter as I will try to explain using two examples.

When I was a dental surgeon, I worked for a while with a wonderful assistant from Uganda. Her English was very good, but when she saw me eating potato crisps at lunch time, she used to ask me whether I was enjoying my “crisips”. The other example concerned a couple of Italian friends who had been living together since they were both 18 years old. Just after their 40th birthdays, they married suddenly. When we asked them why, the lady said in English:

“For physical regions.”

We were surprised. It turned out that what she was trying to say in her Italian accented English was that they had married for FISCAL reasons.

Both my Ugandan assistant and our Italian friend had inserted vowels between two consecutive consonants where they did not exist in the properly pronounced versions of ‘crisps’ and ‘fiscal’. Remembering this, I wonder whether whomever had written the shop sign in Shepherd Bush Market had thought it unnecessary to put in various vowels where they should have been because they believed that readers of their sign would automatically add vowel sounds between some pairs of consonants. This kind of reader would probably read the misspelt signs as follows:

“African customary garments shop”

If this is not the case, then the signwriter needs to improve his or her spelling of English words.

THE NAME MOLESWORTH immediately recalls a naughty schoolboy who cannot spell properly. Nigel Molesworth, a pupil in St Custards, a preparatory school, appears as a character in books by Geoffrey Willans (1911-1958) such as “Down with Skool”, “How to be Topp”, and “Whizz for Atomms”. However, for the Cornish town of Wadebridge, the name Molesworth has other significance.

One of the main shopping thoroughfares in Wadebridge is called Molesworth Street. The Town Hall was opened in 1888 by Sir Paul Molesworth (1821-1889). A pub called The Molesworth Hotel, a former coaching inn housed in a building that dates back to the 16th century, is located on the street named after Molesworth. The pub was only named as it is today in 1817. Previously, it had various names including The Fox, The King’s Arms, and The Fountain.

Wikipedia informs us that:

“The Molesworth, later Molesworth-St Aubyn Baronetcy, of Pencarrow near St Mabyn in Cornwall, is a title in the Baronetage of England. It was created on 19 July 1689 for Hender Molesworth.”

Hender Molesworth (c1638-1689) was a Governor of Jamaica from 1684 to 1687 and from 1688 to 1689. Pencarrow House is just under 4 miles southeast of Wadebridge. Each of the 2nd, 4th,6th, and 8th Baronets represented Cornwall or parts of the county in Parliament. The Molesworths were (are?) major landlords in the area around Wadebridge.

Sir William Molesworth, 8th Baronet (1810–1855), was the grandfather of Sir Paul, who opened the Town Hall in 1888. This edifice bears a weathervane in the form of a steam railway locomotive. After undertaking a ‘Grand Tour’ of Europe, which lasted from 1828 to 1831, William made his way to Pencarrow, where he:

“…devoted time to establishing the Wadebridge-Bodmin Railway company. He engaged Hopkins the civil engineer to survey the land for the route with the prospectus for the formation of the Railway Company drawn up by Mr Woollcombe, from the family’s firm of solicitors.” (www.pencarrow.co.uk/story/sir-william-molesworth/)

This railway opened in 1834, was the first steam railway in Cornwall. It continued in service until 1979. The tracks have been removed but some of Wadebridge’s station buildings have been preserved,

William became interested in radical politics. In 1832, he was elected Member for East Cornwall, and re-elected in 1835. As an MP, he:

“…had joined a group named the ‘Philosophical Radicals’ who advocated various reforms such as universal education, disestablishment of the church and universal suffrage.”

Between 1837 and 1841, William, having alienated his Cornish electorate, sat in the House of Commons, representing Leeds. After falling out with his Leeds constituents on account of his views on foreign policy, he retired to Pencarrow, where he dedicated his time to improving the gardens.

In 1844, William married a widow, an opera singer Andalusia (née Carstairs), who died in 1888. The year after his marriage, William was elected MP for London’s Southwark constituency, a seat he held until his death. Amongst his positions whilst representing Southwark, he was Secretary for The Colonies during the last few months of his life. He had wished to be buried in his grounds in Pencarrow, but instead he was buried in London’s Kensal Green Cemetery.

Sir William and his family are deeply involved in the history of Wadebridge and it is right that the Molesworth name is so prominent in the town. From now onwards when I hear or read the name Molesworth, a naughty schoolboy with spelling problems will not be the only thing that springs to mind.

Waiting for a train

Training with a weight:

Sounds same, but meanings differ

When two words have the same spelling or same pronunciation, they are called ‘homonyms’

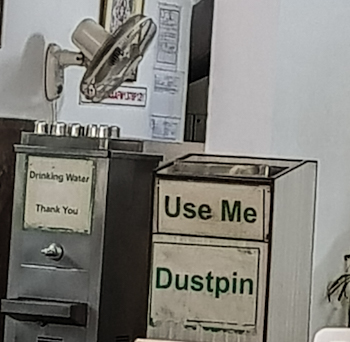

All over India you can see variations in the spelling of English words. Here are some examples I saw today in Bangalore.

Here the word ‘naughty’ has been spelled semi-phonetically.

Here, b and P have been mixed up. The consonants B and P are formed similarly when spoken.

This shop sign demonstrates a variety of different kinds of spelling errors. (By the way, ‘chats’ are slightly cooked vegetables or raw fruits dressed with spicy powders.)

Remember that although English is one of India’s national languages, for many shop owners it is a foreign language. Hence, the diversity of spellings of common English words.