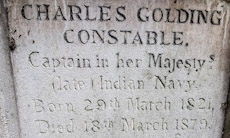

ENCLOSED BY IRON railings, the grave of the artist John Constable (1776-1837) stands at the southern edge of the old part of the churchyard of St John’s Church in Hampstead. The famous painter does not lie alone. He is buried with some other members of his family. One of these people is his second son Charles Golding Constable (1821-1879). I became interested in him when I noticed the words “Captain in her Majesty’s (late) Indian Navy”. The inclusion of the word ‘late’ and its position in the inscription puzzles me.

Charles went to sea as a midshipman in the British East India Company’s navy when he was about 14 years old. According to a genealogical website (www.bomford.net/IrishBomfords/Chapters/Chapter33/chapter33.htm/), he:

“…took to the sea, joined the Indian Marine and eventually became a Captain. Around 1836 he left on his first voyage to China and did not return until after his father’s death so missed his large funeral in London. During the 1850s he gained a place in the reference books for having conducted the first survey of the Persian Gulf. He had to struggle with navigation as a youth so he must have shown considerable determination to be entrusted with this survey. Shortly before his survey the Arab sheikhs bordering the southern end of the Gulf gained their income largely by piracy; this was ended by a treaty or truce arranged by the British, and the Sheikhdoms that signed the truce have been called ever since the Trucial States.” A paragraph in the book “Journey to the East” (published by Daniel Crouch Rare Books Ltd.) related this in some detail:

“Commander Charles Constable, son of the painter John Constable, was attached to the Persian Expeditionary Force, as a surveyor aboard the ship Euphrates. On the conclusion of the war [the First Anglo-Persian War: 1856/57], Constable was ordered to survey the Arabian Gulf, which occupied him from April 1857 to March 1860, with Lieutenant Stiffe as assistant surveyor. The survey (Nos. 2837a and 2837b) which contains the first detailed survey of Abu Dhabi, would become the standard work well into the twentieth century. During the time that Constable was surveying the Gulf, the Suez Canal, one of the greatest civil engineering feats of the nineteenth century was under construction.”

Charles was made a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society.

While ‘surfing the net’, I found out that sketches made by Charles during his travels have been on sale from time to time in auction houses. His drawings were competent but no match for those executed elsewhere by his famous father.

When John Constable died, his eldest son John Charles Constable became responsible for dealing with his father’s estate. He was then a medical student as well as having studied under the scientist Michael Faraday. According to a website concerning his college in Cambridge (Jesus), John Charles, died suddenly in 1839 after contracting scarlet fever at a lecture in Cambridge’s Addenbrooke’s Hospital, at which a patient suffering this disease was being examined. After his father died, he was left “… numerous paintings and works of art, some of which were known to have adorned his rooms in College.” (www.jesus.cam.ac.uk/articles/archive-month-constable-chapel).

In his will, John Charles left his collection of drawings, paintings, and prints to his younger brother Charles Golding Constable. In 1847/48, Charles was responsible for supervising the dispersal of his father’s studio collection of artworks.

Like the rest of his family, parents and siblings, Charles had lived at several different addresses in Hampstead. Although he was buried with other members of the family in Hampstead, I have not yet found out where he resided at the end of his life.