WHEN RABINDRANATH TAGORE (1861-1941) visited China in 1924, he gave a series of lectures in English, which were translated for the Chinese audiences by the talented young poet Xu Zhimo (1897-1931). During a visit to Cambridge (UK) in August 2024, in several shop windows I noticed a book called “Xu Zhimo Cambridge & China” by Zilan Wang. Even though Cambridge has many students and tourists from China, I wondered about it.

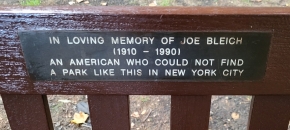

Xu Zhimo was born in Haining (China). He studied law in Beijing, then in 1918 travelled to the USA, where he studied for, and was awarded a degree at Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts. After starting a degree at Columbia University in New York City, he left the USA because he could no longer stand the place. He then travelled to the UK, where he first studied at the London School of Economics, and then at Kings College, Cambridge. It was in Cambridge that he became deeply attracted to poetry, and began writing it. In 1922, he returned to China, where he became an important figure in China’s modern poetry movement. He was a believer in ‘art for art’s sake’ rather than the (Chinese) Communists’ belief that art should serve politics.

When Tagore came to China, the country was in turmoil: there was fighting between rival warlords and the risk of an invasion by the Japanese was great. Xu Zhimo served as one of his oral interpreters, translating Rabindranath’s romantic (English) language into vernacular Chinese. Tagore did not rate his visit to China a great success. He was met with some hostility as Huan Zhao explained in the introduction to an article entitled “Interpreting for Tagore in 1920s China: a study from the perspective of Said’s traveling theory” (Perspectives, Volume 29, 2021 – Issue 4):

“During Tagore’s visit, his initial perceptions of welcome were transformed dramatically into a feeling of rejection, resulting in an unpleasant sojourn. After forty-odd days, Tagore left China, disconsolate, with his mission unaccomplished. Exactly what happened remains unclear. The introductory flyleaf of Talks in China claims his poor reception had much to do with ‘organized hostility from the members of the Communist Party and was labeled as a reactionary and ideologically dangerous.’ Others maintain that Xu, as Tagore’s interpreter, should shoulder much of the responsibility for the visit’s outcome – that Xu’s efforts to enhance his own fame while welcoming Tagore effaced Tagore’s purposes and ideas”

And in the author’s conclusion, the following was written:

“In 1920s China, Tagore’s lectures and Xu’s interpretations faced strong resistance from Chinese intellectuals who sought radical social reform. This resistance interrupted Tagore’s visit and inflicted lasting anguish on his interpreter Xu Zhimo. Although challenged by critics, Tagore’s lectures continued to influence Chinese philosophers, thanks in large part to Xu’s unyielding efforts to expand and explain Tagore’s lectures.”

Xu Zhimo was killed in an air crash in November 1931.

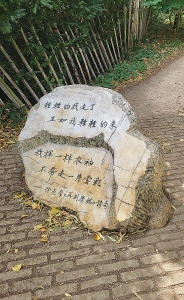

On our recent visit to Kings College in Cambridge, we stopped to look at a large stone on which Chinese writing characters are inscribed. We had passed it on previous visits to the city, but had not investigated it. This time, we noticed a short path leading from the stone into a circular enclosure surrounded bushes and trees. The path is lined with rectangular paving stones on which some lines of a poem by Xu Zhimo is carved. Alternate stones are in Chinese, the others are in English. The words are from Xu’s poem “再别康桥” (Zài Bié Kāngqiáo, which means ‘Taking Leave of Cambridge once more”), which he wrote in 1928. The enclosed area has a small bench upon which we sat, watching a continuous stream of Chinese people visiting the memorial, stopping to look at it respectfully.