LOSING AN ELECTION is probably one of the worst things that happens to politicians today. Several centuries ago, a politician risked facing a far worse fate: decapitation. Such was the ending that was suffered by a 17th century politician who chose to live Hampstead in north London, close to Westminster yet surrounded by countryside.

Sir Henry Vane (c1612-1662) is often referred to as ‘Henry Vane, the Younger’ or ‘Harry Vane’. Born into a wealthy family, he completed his education in Geneva, where he absorbed ideas of religious tolerance and republicanism. His religious principles led him to travel to New England. Between May 1636 and May 1637, he served as the 6th Governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. While in America, he raised a large amount of money to be used for the establishment of what is now Harvard University. Soon, he came into conflict with other colonists. Barratt, an historian of Hampstead, wrote:

“…he soon found that his own ideas of religious independence and those of his friends were not in harmony. Their “tolerance” was shown in a cruel and rigid intolerance of everything that did not fit in with their own narrow Calvinistic views; Harry Vane stood for a larger humanity.”

Harry returned to England and became a Member of Parliament as well as a Treasurer to the Royal Navy (in 1639). He was knighted by King Charles I in 1640.

When the conflict between the Royalists and the Parliamentarians broke out in about 1642, it was hoped that Harry would stick with the Royalists, but he did not. He became a solid supporter of the Parliamentarians. During the Commonwealth that followed Cromwell’s victory in the Civil War (1642-1651), he regained his position of a treasurer to the navy. Harry’s views on various things differed from those of Oliver Cromwell. By this time, Harry had moved to a house in Hampstead, Vane House, where, it is believed, he used to meet with Cromwell, Fairfax, and other prominent Parliamentarians. The poet Milton was also a visitor at Vane House. Barratt relates that when the question of executing King Charles I was being decided:

“…Vane refused to be a party to the sentence, and retired to his Raby Castle property in Durham, one of the estates his father settled on him on his marriage in 1640.”

Vane had married Frances Wray, daughter of Sir Christopher Wray, who was a Parliamentarian.

Harry became concerned when Cromwell barred him from the dissolution of the so-called ‘Long Parliament’ in 1653. Let Barratt expand on this:

“When Cromwell violently broke up the Long Parliament, his most active opponent was Sir Harry Vane, who protested against what he called the new tyranny. It was then that Cromwell uttered the historic exclamation, “O Sir Harry Vane! Sir Harry Vane! the Lord preserve me from Sir Harry Vane!” Vane was kept out of the next Parliament, and, still remaining at Raby, made another attack on Cromwell’s Government, in a pamphlet entitled ‘The Healing Question’. This was a direct impeachment of Cromwell as a usurper of the supreme power of government, and led to Vane being summoned before the Council to answer for his words.”

Harry’s actions led him to be imprisoned on the Isle of Wight.

Following Oliver Cromwell’s death in 1658, Harry returned to public life and his home in Hampstead. He was striving for Britain to become a republic rather than a continuation of the dictatorial Protectorship established by Cromwell and continued by his son Richard.

When King Charles II was restored to the throne, ending the Protectorship, Harry, who had not been party to, or in favour of, the execution of Charles I, was granted amnesty and hoped to live in retirement, contemplating religious matters that interested him, in his Hampstead residence. But this was not to be. Although the King was happy to forgive Harry, some of his advisors were concerned that, to quote Barratt:

“Vane’s ultra -republicanism was probably more objectionable to Charles II. than it had been to the Protector, and Charles had not been established on the throne more than a few months when the arrest of Sir Harry Vane was ordered.”

Harry was taken from his garden in Hampstead by soldiers on an evening in July 1660. After a short spell in the Tower of London, Harry spent two years as a prisoner on the Isles of Scilly. In March 1662, he was brought back to the Tower and faced trial at the King’s Bench. The charge against him was:

“…compassing and imagining the death of the king, and conspiring to subvert the ancient frame of the kingly government of the realm…”

The judges in this unfair trial had no option but to find him guilty. He was executed at the Tower.

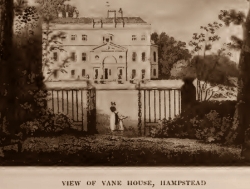

I would not have been aware of this remarkable man had I not spotted a brown and white commemorative plaque in his memory on an old brick gate post on Hampstead’s Rosslyn Hill. The gatepost and a short stretch of wall are all that remains of Harry’s Vane House, which was has been demolished. It was still standing in 1878, by which time it had been heavily modified and:

“…occupied as the Soldiers’ Daughters’ Home. Vane House was originally a large square building, standing in its own ample grounds.” (www.british-history.ac.uk/old-new-london/vol5/pp483-494).

This was connected by a covered arcade to a school for soldier’s daughters. The building which housed the school still stands on Fitzjohns Avenue and has been renamed Monro House. The heavily modified Vane House, in which Sir Harry resided, was demolished in 1972. Its only remains are as already mentioned.

Once again, seeing a small thing whilst strolling around in London has opened a window that has given me a first view of an aspect of history that was almost, if not completely, unknown to me.