THE ORIGINAL SERPENTINE Gallery in London’s Kensington Gardens is housed in a former tea pavilion that was built in 1934. It began to be used as a contemporary art exhibition space in 1970. Since then, it has been showing modern and contemporary artworks in a series of temporary exhibitions. I have been visiting this gallery and its newer branch, Serpentine North, regularly since the 1990s (the North branch opened in 2013). Almost without exception, the art displayed in the Serpentine galleries has been both exciting and adventurous – sometimes quite challenging. The latest exhibition, which is on until the 17th of March 2024 in the original gallery, is of artworks by the American (USA) artist Barbara Kruger, who was born in Newark (NJ) in 1945.

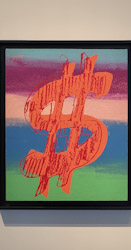

Kruger’s art is not purely visual. It is designed to convey ideas that challenge the viewer to question commonly held contemporary beliefs in an eye-catching, often witty way. The exhibition, “Thinking of You. I mean Me. I mean You” consists of 12 art installations that reference or parody everyday things such as advertising, magazine illustration, video art, social media, the Internet, and other media that bombard us on a daily basis. Each of them present messages that subvert political ideas, the moral code, and the meanings of words. Kruger makes much use of video techniques. Several of the exhibits have words projected sequentially to make up sentences. Often, the words change on the screen to alter the perceived meaning of the text being projected. However, her art is not simply all about words and their meanings in different textual environments. The words are harmoniously accompanied by intriguing visual images, often continuously changing.

Although the exhibition is about words and their usage and varying meanings, words alone cannot describe this exhibition adequately. Therefore, if you can, it is worth taking a look at this interesting – nay, challenging – show. Having viewed the show, I was heartened to discover this artist from America who is perceptive enough to see where her country is heading and brave enough to criticise the political direction in which it appears to be moving. After seeing her exhibition, I would hazard a guess that she will not be voting for Mr Trump.