BETWEEN OUR FRIENDS’ house in Richmond and Richmond Bridge, which crosses the River Thames, is but a short walk, taking not more than five minutes at a leisurely pace. Yet, during this brief walk that I took yesterday, on the day that my mother would have been one hundred years old, I spotted three old things that were new to me.

The first thing I noticed for the first time is a small single-storeyed building on Church Terrace close to the Wakefield Road bus station. What attracted me to it was a stone plaque set within its stuccoed façade that stated:

“The Bethlehem Chapel built in the year 1797.”

It is still in regular use. I picked up an information leaflet from a plastic container next to its locked door, and this provided me with some information about the place, whose façade looks original but has otherwise been substantially updated. The interior of this non-Conformist place of worship appears to be similar to what it was when it was first built but considerably restored and modernised a bit (see images of the interior on the video: https://youtu.be/kIYuxaMyZsA).

John Chapman, market gardener of Petersham, where currently the fashionable, upmarket Petersham Nursery flourishes, built the chapel for an independent Calvinist congregation. It was opened by William Huntingdon (1745-1813), a widely known self-educated Calvinist preacher, who began life as a ‘coal heaver’ (https://chestofbooks.com/reference/A-Library-Of-Wonders-And-Curiosities/William-Huntingdon.html). Because of this, the chapel, which is the oldest independent Free Church in the West of London, is also known as the ‘Huntingdon Chapel’. By Free Church, the leaflet explains:

“We do not belong to any denomination. We are an Independent Free Church, which means that we are not affiliated to any organised body like the Church of England, Methodists or Baptists etc.”

More can be discovered about the congregation and its beliefs on the chapel’s informative website (http://bethlehem-chapel.org/index.html).

Between the chapel and the bridge, there is an Odeon cinema with a wonderful art deco façade. This was designed by the architects Julian Leathart (1891-1967) and W F Granger and was opened in 1930. It was originally named the ‘Richmond Kinema’, but this was changed to the ‘Premier Cinema’ on the 29th of June 1940:

“… to enable the removal of the Richmond name on the cinema, in case German parachutists landed nearby.” (http://cinematreasures.org/theaters/6260)

In May 1944, the cinema’s name was changed to the ‘Odeon’. Before it was converted to a triple screen cinema in 1972, its huge auditorium was able to accommodate 1553 seated viewers.

Crossing the main road in front of the cinema, we descend Bridge Street towards Richmond Bridge, but before stepping onto the bridge, we turn left and enter Bridge House Gardens. This open space was the site of the now demolished Bridge House, which was the sometime home of a Jewish family:

“Moses Medina (nephew of Solomon Medina and three times treasurer of Bevis Marks) lived at Bridge House from the 1720s to 1734, having lived previously at Moses Hart’s old house. Abraham Levy lived there from 1737-1753. Levy was a wealthy merchant of Houndsditch.” (www.richmondsociety.org.uk/bridge-house-gardens/).

Solomon Medina (c1650-1730) followed the future William III to England and became “…the leading Jew of his day” according to Albert Hyamson in his “History of The Jews in England” (publ. in 1928), a book I found in the second-hand department of Blossom Book House in Bangalore. Medina became the great army bread contractor in the wars that followed his arrival in England. He was knighted for his services, thus becoming the first professing Jew to receive that honour. His reputation was called into question because it was alleged that he had bribed John Churchill (1650-1722), the First Duke of Marlborough (see “Marlborough” by Richard Holmes, publ. 2008). Moses, his nephew, was a rabbi at the Bevis Marks synagogue in London and thrice its treasurer and also involved in his uncle’s bread contracting, supplying this food to Marlborough’s forces in Flanders (https://forumnews.wordpress.com/about/bank-of-england-nominees/).

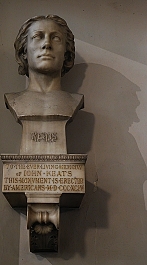

Bridge House was demolished in 1930 to create the present area of parkland. Well, I did not know about the Medina connection with Richmond when we visited the Bridge House Gardens. What attracted my attention as soon as I set foot in the small park was the bust of a man looking across a flight of steps and out towards the river below it.

The bust depicts a man wearing a heavily decorated military uniform with tasselled epaulettes. It is a representation of General Bernado O Higgins (Bernado O’Higgins Riquelme), who was born in Chile in 1778 and died in Peru in 1842. Bernado was an illegitimate son of Ambrosio O’ Higgins (c1720-1801), who was born in Sligo (Ireland) then became a Spanish officer. He became Governor of Chile and later Viceroy of Peru. Bernado’s claim to fame is that he was a Chilean independence leader who freed Chile from Spanish rule after the Chilean War of Independence (1812-1826). He is rightfully regarded as a great national hero in the country he helped ‘liberate’. But, what, you might be wondering, is his connection with Richmond?

O Higgins studied in Richmond from 1795 to 1798 and while doing so, lived in Clarence House, which is at 2 The Vineyard, Richmond. Whilst in Richmond, he studied history, law, the arts, and music (https://www.davidcpearson.co.uk/blog.cfm?blogID=632) and met Francisco de Miranda, who was active amongst a London based group of Latin Americans, who opposed the Spanish crown and its rule of colonies in South America. The bust was inaugurated in 1998 to celebrate the 200th anniversary of the departure of O’ Higgins from Richmond. Our friends told us that once a year, a delegation of Chileans arrives by boat at Bridge House Park to celebrate joyously in front of the bust of their national hero. As they arrive, another boatload of people arrives to join the celebration: members of the administration of the Borough of Richmond.

No far from the memorial to the great O’ Higgins, there is another remarkable sight close to the river: a tree with a small notice by its roots. To me, it did not look exceptional, but the notice explains that this example of Platanus x hispanica (aka ‘London plane’):

“… is the Richmond Riverside Plane, the tallest of its kind in the capital, and is a great tree of London.” First discovered in the 17th century, this hybrid of American sycamore and Oriental plane, was planted a great deal in the 18th century. The plane growing near to the bust of O’ Higgins has a record-breaking height. What I cannot discover is the date on which the notice was placed. So, being the sceptic that I am, I wonder if any other plane trees in London have exceeded the height of this one since the notice was installed.

All of what I have described can be seen in less than ten minutes, but as I hope I have demonstrated, a great deal of history is encapsulated in that tiny part of Richmond.