SEVEN ROADS MEET at a point in London called Seven Dials. A column with seven sundials attached to it stands in the middle of the circle where they meet. Long ago, on the 5th of October 1694, the writer and diarist John Evelyn (1620-1706) noted that he went:

“…to see the building beginning near St. Giles’s, where seven streets make a star from a Doric pillar placed in the middle of a circular area; said to be built by Mr. Neale, introducer of the late lotteries, in imitation of those at Venice, now set up here, for himself twice, and now one for the State.”

The pillar with sundials facing in seven directions was erected in 1694 by Edward Pierce (1630-1695) and Thomas Neale (1641-1699). Pierce was a sculptor, architect, and stonemason. Neale was a Member of Parliament for 30 years; Master of the Mint; gambler; and entrepreneur. His achievements included:

“…development of Seven Dials, Shadwell (including brewing and Navy victualling), East Smithfield and Tunbridge Wells, to land drainage, steel and papermaking, mining in Maryland and Virginia, raising shipwrecks, to developing a dice to check cheating at gaming. He was also the author of numerous tracts on coinage and fund-raising and was involved in the idea of a National Land Bank, the precursor of the Bank of England. The extent of his interests – as a prominent Hampshire figure, as a member of the Royal Household, as a long-standing MP serving on dozens of Committees and as the promoter of an extraordinary plethora of projects” (www.sevendials.com/history/thomas-neale-1641-1699).

In July 1773, the column bearing the seven dials was removed because it was believed that there was a substantial amount of money hidden beneath it, so wrote Peter Cunningham in his Handbook of London (1850). None was found. Another theory suggests that the pillar was removed:

“… to rid the area of the undesirables who congregated around it. The remains of the column were later moved to the garden of the architect James Paine (Junior) at Sayes Court, Addlestone, but not re-erected.” (www.sevendials.com/resources/Seven_Dials_History_of_the_Area_by_Dr_John_Martin_Robinson.pdf)

It was not until 1989 that the demolished column was replaced. It was reconstructed according to Pierce’s original design that is lodged in the British Library. The new column was unveiled by Queen Beatrix of the Netherlands on the 29th of June 1989.

The entrepreneur Thomas Neale would have approved of a venture that commenced in his Seven Dials district in 1976. That year, Nicholas Saunders (1938-1998) opened his Whole Food Warehouse in a disused warehouse in Neal’s Yard (formerly ‘Kings Head Court’), named in memory of Thomas Neale. In Saunder’s words:

“I decided to start a wholefood shop which I would like myself – one that was cheap, efficient and would not make customers feel bad because they could not recognise a mung bean. At that time wholefood shops were mostly of the hippy style – folksy looking with open sacks and used paper bags; nice meeting places for the in-groups but hopelessly inefficient, expensive and tending to make ordinary people feel like intruders.” (https://nealsyardlondon.co.uk/history/).

His venture proved successful. Various other businesses including Neal’s Yard Remedies, Neal’s Yard Dairy, Casanova & daughters, and Wild Food Café, opened nearby. Saunders wrote:

“The Yard has developed into a social scene. Even though the businesses are each independent, everyone who works in them, and many of the regular customers, identify with the place. In fact most of the workers are customers who had asked for a job. My old idea of a village community has manifested in the form of a community of small businesses, each one individual and free to go its own way. It is rather like a family, with me as a father and the businesses as my grown-up children.”

Although we made our last visit to Neal’s Yard in the middle of the covid19 pandemic, when the place was empty and closed, it is safe to say that the Yard continues to be a vibrant ‘social scene’ and its shops are still thriving despite the fact that shops supplying ‘whole foods’ have multiplied considerably since Neal’s Yard was established. Saunders is commemorated in the Yard by a wall mounted plaque.

Apart from selling food and remedies, Neal’s Yard was home to the film studio run by Michael Palin and Terry Gilliam between 1976 and 1987. It was here that they edited the Monty Python series of films.

One of the entrances to Neals Yard is an alleyway leading from Monmouth Street (formerly ‘Great St Andrew Street’), one of the seven streets leading to the Seven Dials. The street is home to one of London’s older still existing French restaurants, Mon Plaisir, which is close to Neals Yard and was founded long before Saunders established his venture. The brothers David and Jean Viala started the eatery in the 1940s.

My parents moved from South Africa and settled in London in the late 1940s, by which time Mon Plaisir was serving customers. I do not know when my parents first ate there, but during my childhood I remember it as being one of their favourite places at which to to eat out. Until 1972, when new management took over the restaurant, Mon Plaisir occupied one shopfront. Its characteristic quirky décor rich in everyday French posters and other ephemera remains substantially unchanged since the 1940s. As a child during the 1960s, I was taken there infrequently. I remember liking it. One thing that I recall was that the toilets were approached through a doorway at the end of the restaurant furthest away from the street. An artist’s palette was nailed above the doorway. It bore the words “Le Pipi Room”. On a visit made this century to the enlarged restaurant, I noted that the sign had disappeared. When life returns to ‘normal’ again, another meal at Mon Plaisir is on our ‘to do’ menu.

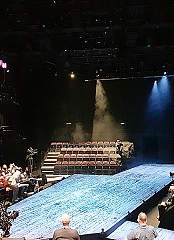

During my childhood, the Seven Dials did not make any impression on me. I knew about Mon Plaisir, but never ventured south the few yards to the Dials. With the opening of the Donmar Theatre on Earlham Street, another of the roads leading to the Dials, in 1977, which we have visited often, the Seven Dials entered my London radar.

Before ending this somewhat rambling piece, here is a true story about the theatre. Soon after it opened, an American friend, a keen theatregoer who was midway in age between my parents and me, invited me to join her at a performance at the Donmar. It was a play with a Chinese theme. We were seated in the front row, literally on the stage. My friend who had long legs, stretched them out onto the stage and the actors had to take care not to trip over them. Halfway through one of the acts, my friend began fumbling in her large bag and withdrew a thermos flask. She removed the lid, which served as a cup, and gave it to me to hold. Then, she filled the cup with hot soup, which she proceeded to drink whilst the drama unfolded in front of us. I often wonder what the actors, who were so near us, thought when they saw a member of the audience enjoying her picnic in front of them.

The Seven Dials and the streets radiating from the column are full of fascinating buildings, some old and others new and there are plenty of shops to explore apart from those pioneering wholefood shops in Neals Yard. If you can manage to get a ticket to the Donmar, and this is quite hard if you are not on their advance booking scheme, then it is often worth watching a performance there.