In the 1980s, I visited my friends in the former Yugoslavia frequently. Also, I visited Albania and what is now independent Kosovo. During my trips, I picked up a large vocabulary of Serbo-Croat, including quite a selection of outrageous swear words. Grammar has always been beyond me in foreign languages, and often in my own. My interest in Albania and my brief visits to Albanian-speaking parts of the Balkans resulted in me acquiring some vocabulary in Albanian, but far less than in Serbo-Croat. Until the 1990s, I believed that my fragmentary knowledge of these languages would be useless outside the Balkans.

Prizren in Kosovo, pre-1990

During one trip to Belgrade, a friend arranged for me to be an observer in a clinic of a leading oral surgeon. I turned up at a large hospital and spent a couple of hours watching the surgeon reviewing a series of his patients. Although I was grateful to be allowed to watch the great man, I learned little that was relevant to practising dentistry. However, one aspect of this clinic interested me greatly. As each patient entered the consulting room, he or she presented the surgeon with a gift: a bottle, a large piece of cheese, a ham, etc.

The last patient to enter, a man in a somewhat shabby suit, entered and sat in the dental chair without having presented a gift. After his mouth had been examined, the surgeon took the patient and me out into a corridor. We walked through the hospital to a room with locked doors. My host unlocked it, we entered, and he locked the doors behind us. After a brief conversation, the patient handed the surgeon a small brown envelope, which he thrust into his jacket pocket. Then, after the doors were unlocked, the patient went one way, and we went another way. As we walked along the corridor, my host patted the pocket containing the envelope, and before bidding me farewell, said: “Pornographic photographs.”

Poster of Marshal Tito in Sarajevo, Bosnia in the 1980s

My last visit to Yugoslavia was in May 1990. Soon after that, wars broke out in the Balkans, and the former Yugoslavia disintegrated painfully to form smaller independent states. In the early to mid-1990s, there was terrible strife in Bosnia. Many people fled as refugees to places including the UK. In the late 1990s, Kosovo suffered badly from warfare between the Serbs and the ethnic Albanians. Many of the latter fled to the UK.

I moved from one dental practice outside London to another in London, an inner-city practice, in 2001. A significant number of my patients there had come from the former Yugoslavia as refugees. I was the only person in the practice who could greet them in Serbo-Croat or Albanian. Maybe, I was only one of a few dentists in London at that time who had this ability.

To the Albanian speakers my vocabulary was restricted to words such as ‘hello’ and ‘good-bye’, which brought smiles to their faces. Following a trip to Communist Albania in 1984, I recalled the Albanian words of political slogans such as “Long live Enver Hoxha”, “Enver’s party”, and “Long live the Peoples’ Party of Albania.” As many of my Albanian patients had come from Kosovo rather than Albania, these slogans meant little to most of them.

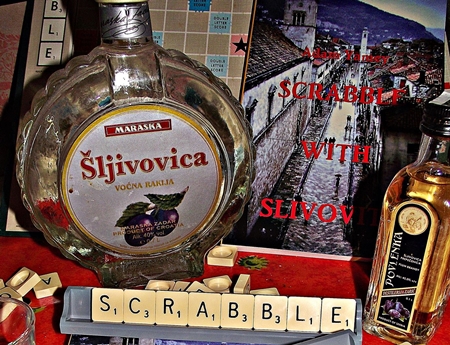

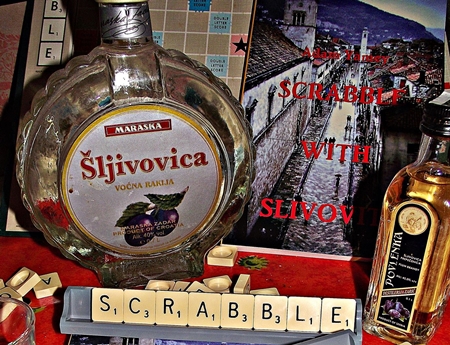

Travnik, Bosnia, 1975

My limited Serbo-Croat was more extensive than my Albanian. I could entertain some of my Bosnian and Serbian patients with polite small-talk. Many of the ex-Yugoslav patients, like those I had seen long before in Belgrade, brought me gifts. Even those, with whom I felt I was not getting along with well, brought me, usually, bottles of home-made alcohol (e.g. rakia, slivovitz, and loza) that had been distilled by relatives who had stayed behind in the former Yugoslavia. These strong alcoholic drinks were delicious, smooth, and delicately flavoured. One fellow plied me with DVDs of the latest Hollywood and other films that he had ‘pirated’. One lovely lady from Bosnia presented me with a pair of earrings, which her uncle had made, to give to my wife. She wears these often, and she is very grateful.

Many Middle-Eastern patients also felt that it was appropriate to bring me gifts. Thus, a lot of delicious baklava and other similar confections came my way. Delicious as these were, they were neither good for my teeth nor for my general health. A Hungarian family kept me supplied with large gifts of paprika powder, and there was a Romanian gentleman who brought me nice bottles of wine. Incidentally, the only words of Romanian I know are “thank you” and “railway timetable”. Once, we employed a Romanian dental nurse and I told her my Romanian party-piece “Mersul trenurilor.” She pondered for a moment and then replied “Ah, the programme of the trains.”

Once, my dental nurse, a friendly West Indian lady, and I were standing near a window facing the main road when a delivery van stopped nearby. A man was delivering trays of baklava to a nearby shop. I said to my nurse: “Why don’t you see if he’ll give us some to try?” She returned with a tray of baklava. Carelessly, because I was in a hurry to see my next patient, I put a large lump of baklava into my mouth, and then bit hard on it. As I was doing this, I heard a deafening bang in my head. The baklava was not too fresh. I had split a molar tooth into two parts, the smaller of which was loose in my gum.

Baklava

Unlike this disastrous piece of confectionary, the gifts kindly given to me by my patients did no harm. Furthermore, what I believed to be a useless tiny vocabulary of Balkan languages proved to be quite useful.

Finally, you might still be wondering whether anybody ever took me aside to present me with an envelope containing pornographic photographs. To satisfy your curiosity, I can tell you that nobody did.