ALMOST AS SOON as English people began visiting India, and later colonising it, they took an interest in the flora of the Indian Subcontinent. Their interest was both scientific and commercial: looking for plants that could be exploited to make a profit. Many of the early English explorers of India’s flora worked in an era before photography was invented, or in the early days before colour photography became possible. Instead of making photographs of botanical specimens, detailed drawings and paintings of plants were created. Until I visited an exhibition at Kew Gardens, which runs until 12 April 2026, I believed that all the intricately detailed botanical images had been created by English and other European people.

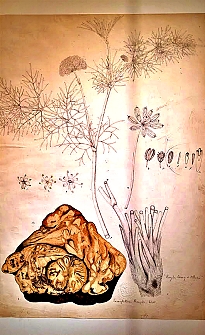

The exhibition, “The Singh Twins: Botanical Tales and Seeds of Empire”, is divided into two related but quite different sections. One section contains colourful, contemporary artworks by the Singh Twins. The other, subtitled “Flora Indica: Recovering the lost histories of Indian botanical art” contains 52 botanical illustrations by Indian artists commissioned by British botanists between 1790 and 1850. Each one of them is rich in detail, delicately drawn and/or painted, and a delight to behold. Not much is known about the Indian artists apart from their names, and where they were based. The artists were both Hindus and Muslims, and their pictures combine traditional Indian draughtsmanship with the kind of scientific realism required by the English botanists who commissioned them. Compared to other Indians employed by British botanists, they were well paid, receiving up to £500 per month in today’s money.

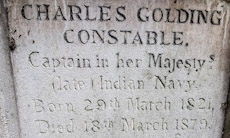

Most of the Indian artists, whose works were on display were based in Bengal: most in Berhampur, others in Calcutta and Darjeeling. Other artists were in Burma, Saharampur, and Nepal. All of them were male. Over 7500 drawings of flora in South Asia were commissioned by the East India Company, and were created entirely by Indian artists. Some of these images reached Kew in 1879 from the Company’s India Museum, established in London in 1801 and closed for good in 1879.

The exhibition is well-displayed with informative labels. It is in the Shirley Sherwood Gallery of Botanical Art. This contemporarily designed edifice is close to the much older Marianne North Gallery, which houses a huge collection of botanical images created by Marianne North (1830-1890). Although her paintings are superb, those by the Indian artists in the exhibition have a certain delicacy that is lacking in many of North’s often quite bold depictions of flora.

The “Flora Indica” exhibition is showing alongside the Singh Twins’ artworks, which are imaginative, witty, and provide a satirical view of the consequences of European colonisation, particularly of India and Africa. Rich in floral details, the images complement those created much earlier by the Indian botanical artists.