GANJIFA IS A traditional art of decorating playing-cards. Ganjifa cards originated in Persia and spread to India. They can be rectangular but are often circular. Traditionally, the Indian cards were decorated with scenes from the Ramayana.

In the 1980s, Indian artist Raghupati Bhat revived the Mysore tradition of ganjifa painting. The Victoria and Albert Museum in London has a set of his ganjifa cards. Images of these are projected on a wall of Kaash Space, a gallery in Bangalore’s Berlie Street. They form part of a superb exhibition of later works by Bhat, all of which are developments of his earlier ganjifa artworks.

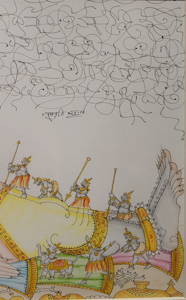

Raghupati Bhat’s drawings and paintings depict mythological stories from the Ramayana. All of them are exquisitely executed and filled with minute details. A set of four painted miniatures are painted with dyes made from natural products, using single hairs from paint brushes to achieve the great detailing within them. In many of his line drawings, Bhat included delicate, beautiful ‘doodles’ in addition to the pictures’ main subjects. All in all, the exhibition includes a fine selection of the artist’s intricately executed creative interpretations of episodes and characters in the Ramayana.

In addition to Bhat’s works, the exhibition includes three other artists’ works: some photographs, some paintings, and two beautiful inlaid wood panels. These other artists’ works were inspired by those of Raghupati Bhat.

This wonderful exhibition continues until 21 December 2025, and should not be missed if you happen to be in Bangalore.