A city must

Keep changing quickly to survive

The passage of time

HAMPSTEAD IS RICH in historical curiosities. One of them is an unexceptional little road that has an interesting story.

Just south of Tesco’s supermarket (the former Express Dairy) on Hampstead’s Heath Street there is a narrow cul-de-sac called Yorkshire Grey Place. It enters Heath Street across the road from The Horseshoe pub and Oriel Place. I have often wondered about this short, uninviting blind-ended lane and its history. Just under 50 yards in length, it runs west from Heath Street.

At long last, I began looking on the Internet for some history (if any) of this bleak little roadway lined on both sides with high buildings. It gets its name from a pub that used to exist near it – The Yorkshire Grey. The pub was already in existence by 1723, but was demolished in the 1880s (https://londonwiki.co.uk/Middlesex/Hampstead/YorkshireGrey.shtml) – in 1886, according to FE Baines in his “Records of Hampstead” (publ. 1890). An online history of Hampstead (www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/middx/vol9/pp15-33) provided the following information about the pub and its surroundings:

“North of Church Row the Yorkshire Grey had been built by 1723 and cottages called Evans Row probably faced it c. 1730. In 1757 the inn and 14 houses occupied by a brickmaker, clockmaker, carpenter, apothecary, and others were ‘late freehold’ but in 1762 they were described as copyhold (one alehouse, two houses, and 11 cottages).”

This area was one of the slums of Hampstead – it was devoid of water supply and drainage.

During the planning and construction of Fitzjohns Avenue, which began in 1875 and was only completed by about 1887, there was some discussion about whether it should end on the High Street or give direct access to the road up to Hampstead Heath. Prior to the late 1880s, the recently built Avenue stopped south of Hampstead village. Its route from there into the centre of Hampstead village was subject to some controversy. This was described in “Hampstead, Building a Borough 1650-1964” by FML Thomson, as follows:

“… The shopkeepers in the High Street feared loss of trade if any traffic was diverted to a new route, and held out for a scheme which would debouch Fitzjohn’s Avenue into High Street at the King William IV ; while the gentry wanted the direct route to Heath Street and the Heath, arguing that this gave a bit of slum clearance of Bradley’s Buildings, Yorkshire Grey Yard, and Bakers’ Row as a bonus. The dissension continued when the scheme was revived with a number of public meetings in 1881, dominated by the gentry element which was increasingly exasperated at having its carriages bottled up in Fitzjohn’s Avenue without any proper exit.”

As it turned out, the “gentry element” had their way, and the slum clearance that affected Yorkshire Grey Yard was carried out – the pub disappeared as a result. In relation to this, the online history of Hampstead, already quoted revealed:

“In 1883 the Metropolitan Street Improvement Act authorized redevelopment of the whole area at the joint expense of the local authority and M.B.W. In 1888 High Street was widened, Fitzjohn’s Avenue (then Greenhill Road) was extended to meet Heath Street, and soon afterwards Crockett’s Court, Bradley’s Buildings, and other slums, including Oriel House and other tenemented houses, were replaced by Oriel Place, shops, and tenement blocks.”

The pub has long gone, but I managed to find two pictures depicting it. One is a painting showing the place in about 1863 (https://artuk.org/discover/artists/lester-harry). It was the work of Harry Lester. The other is a black and white photograph in the book by FE Baines, which was published a year after the pub was demolished. A detailed map surveyed in 1868 showed that the pub was quite a large building with a substantial yard next to its east facing façade. To its west, the yard opened on Little Church Row (now part of Heath Street). This and a blind-ending road called Yorkshire Grey Yard are shown on the map. Immediately south of the pub, there was another cul-de-sac running from east to west – it was unnamed. I believe that this is what is now called Yorkshire Grey Place.

The map drawn in 1868 shows the layout of the area around today’s branch of Tescos before Fitzjohn’s Avenue was conceived. Another map drawn in 1915 shows how the topography of the area changed following the completion of the Avenue. The Yorkshire Grey pub existed before the nearby, still existing, Horseshoe pub was established – it appears on the 1915 map. Originally named ‘The Three Horseshoes’, it moved from Hampstead High Street to its present address in 1890. Had the Yorkshire Grey pub survived, it would have been about 110 feet away from the Horseshoe.

Once again, wondering what is in a name – in this case Yorkshire Grey Place – has opened my eyes to an interesting bit of the history of Hampstead. Finally, it is interesting to note that the Victorian building that houses Tesco’s was built in 1889 – three years after the Yorkshire Grey pub was demolished to make way for buildings along the northern continuation of Fitzjohns Avenue. So, next time you are queuing to pay in Hampstead’s Tesco, remember that you are standing on land where once the patrons of the Yorkshire Grey once trod.

You can read much more about Hampstead and its surroundings in my book, which is available from Amazon:

https://www.amazon.com/BENEATH-WIDE-SKY-HAMPSTEAD-ENVIRONS/dp/B09R2WRK92/

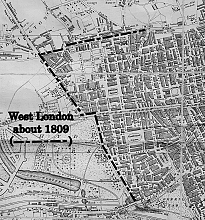

ANYONE FAMILIAR WITH London will know that except for some parkland, the city is a built-up urban environment all the way west from Marble Arch to Acton and further beyond. This is also the case from Hyde Park Corner to Heathrow Airport. However, this has not always been the situation.

When John Rocque (1709-1762) drew his detailed, accurate maps of London in the 1740s, Paddington was a small village separated by open countryside from what was then London. In those days, Kensington was a village reached from London by a country road flanked on its northern edge by Hyde Park. And from Kensington to Hammersmith would have been a ride along a road running between a series of agricultural fields and orchards. And to the north of Hammesrsmith, Shepherds Bush was an open space around which there were only a few well-separated houses. And as for Notting Hill Gate, Rocque did not even bother to name this road junction in the middle of the countryside.

By 1826/27, when C & J Greenwood published their detailed map of London, Earls Court was still a country hamlet; Kensington a small town; and there was barely any development around what is now Notting Hill Gate. However, by 1826 Paddington was beginning to grow and was no longer separated from Marylebone by open countryside. Additionally, the northern edge of the eastern end of Bayswater Road was losing its rural nature and being built upon.

In brief, as the 19th century progressed, London spread west. As it did so, urban development covered what had been open countryside and places that had been separated from London began to become part of it. Places like Kensington, Earls Court, Shepherds Bush, Hammersmith, and places further west were no longer separated by open countryside. Instead, they became engulfed by the expanding metropolis.

My book “BEYOND MARYLEBONE AND MAYFAIR: EXPLORING WEST LONDON” describes in detail how the villages and towns to the west of Park Lane and what is known as ‘The West End’ became engulfed by London’s westward growth. It reveals the history of these places; what they are like today; and what remains of their existence before they became joined to London, as it spread from Mayfair and Marylebone to Heathrow and beyond.

BEYOND MARYLEBONE AND MAYFAIR: EXPLORING WEST LONDON

By Adam Yamey

is available as an illustrated paperback and Kindle from Amazon:

BEFORE THE YEAR 1800, the West End was truly the western end of London. West of Mayfair and Marylebone, there was countryside: woods, fields, private parks, farms, stately homes, villages, and highwaymen. After the beginning of the 19th century, the countryside began to disappear as villages grew and coalesced and the city of London expanded relentlessly westward. What had been rural Middlesex gradually became the west London we know today. My new book, illustrated with photographs and maps, explores the past, present, and future of many places, which became absorbed into what is now west London: that is London west of Park Lane and the section of Edgware Road south of Kilburn. Some of the places described will be familiar to many people (e.g., Paddington, Kensington, Fulham, and Chelsea). Other locations will be less known by most people (e.g., Acton, Walham Green, Crane Park, Harmondsworth, and Hayes). Many people have seen the places included in my book when they have looked out of the windows of aircraft descending towards the runways at Heathrow, and many of them will have passed some of these places as they travel from Heathrow to their homes or hotels. My book invites people to begin exploring west London – a part of the metropolis less often on tourists’ itineraries than other areas. “Beyond Marylebone and Mayfair: Exploring West London” is aimed at both the keen walker (or cyclist) and the armchair traveller.

Beyond Marylebone and Mayfair: Exploring West London is available as a paperback from Amazon here:

https://www.amazon.co.uk/BEYOND-MARYLEBONE-MAYFAIR-EXPLORING-LONDON/dp/B0B7CR679W/:

LONDON’S WEST END includes the part of the city that contains areas such as Chinatown, Theatreland, Covent Garden, Leicester Square, Oxford Street, Mayfair, Soho, Fitrovia, and Bond Street. Before the 19th century, the western boundary of London was Park Lane, which runs along the west edge of the West End.

Until the end of the 18th century and even during the early years of the 19th, west of Park Lane and the West End was the Middlesex countryside, which was dotted with villages such as (for example) Paddington, Kensington, Chelsea, Hammersmith, Fulham, Acton, Ealing, and Southall. In between these then separated places there were farms, heathlands, parks, stately homes (such as Chiswick House and Osterley Park), and highwaymen.

During the 19th century, several things happened. London expanded in all directions and spread into what had been countryside. The small villages in Middlesex grew in size. Some of them coalesced. Canals and railways were built, and along with them, building in areas that had previously been rural, caused them to become urban. In brief, London spread relentlessly westward. What was called the West End, and is still so-called today, was no longer the west end of the city of London.

Although many previously rustic settlements (such as Paddington and other places mentioned above) became engulfed in the metropolis, most of them have retained at least a few reminders of their pre-urban past. Currently, I am putting the finishing touches on a book about London west of the West End. In it, I hope to help readers discover more about London’s western spread and what has survived it (despite being surrounded by the city’s western expansion).