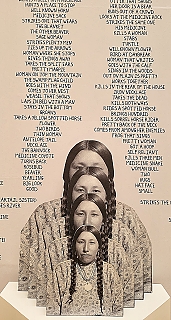

PHOTOGRAPHY HAS LONG been an artistic medium for expressing protest. This is well exemplified by photographic images on display at the excellent “Women in Revolt” exhibition, which is on at London’s Tate Britain until the 7th of April 2024, and is well worth seeing. Running concurrently with this. is an exhibition at the South London Gallery (in Peckham) – “Acts of resistance: photography, feminisms and the art of protest”, which is on until the 9th of June 2024.

As its title suggests, the show at Peckham consists mainly of exhibits that make use of photography. There are also several digital items. The subject matter deals with matters that concern feminists (and ought to concern everyone) including rape, abortion, genital mutilation, other forms of violence against women, and so on. Unlike the exhibition at Tate Britain, which deals mainly with feminist activities in Britain during the 1960s to 1980s, this show was to coin a phrase ‘art sans frontières”, and bang up to date. The exhibition has as its inspiration the words that the artist Barbara Kruger used in 1989:

“Your body is a battleground”.

Incidentally, there is an exciting exhibition of Kruger’s work at the Serpentine South Gallery (in Kensington Gardens) until the 17th of March.

The exhibition at Peckham (to quote the gallery’s website):

“… explores feminism and activism from an international and contemporary perspective. Looking at different approaches to feminism from the past 10 years, the show highlights shared concerns including intersectionality, transnational solidarity, and the use of social media and digital technology as a tool for change.”

It includes works by at least 20 artists, some of them working as collaborators. Their creations are displayed well both in the gallery and its annexe nearby in a disused fire station. Put simply, the works on display at Peckham have a far more visceral impact than those being shown at Tate Britain, which in many cases appeal more to the brain than to the heart. Even if you ignore the messaging conveyed by the artists in the works at Peckham – and this is not easy to do – their visual impact is magnificent. They are works of art as well as being tools of protest. This is an exhibition well worth making the trek out to Peckham!