BETWEEN 1983 AND 1994, I owned a house in Gillingham, Kent. Number 148 Napier Road was a detached dwelling with a narrow garden that stretched 180 feet behind it. Most of this long stretch was covered with grass. After I first moved into the house, I purchased an electric lawn mower, and regularly trimmed the lawn. All went well at first. However, after a few months and several mowing sessions, I found that when I was cutting the lawn my eyes streamed, and I sneezed uncontrollably. I tried wearing a facemask when mowing, but this did not relieve the symptoms. Eventually, I decided not to bother mowing the lawn.

The grass grew. So did the anger of my immediate neighbours, both of whom were elderly and believed in tidy gardens. One of them said that because my lawn was so unkempt, insects were travelling from it into her garden and destroying her plants. She was so upset by this thought that she did something extremely unwise. One summer evening, I returned home after nightfall, and because the weather was pleasant, I decided to spend a few minutes in my back garden. It was dark. I sniffed, and believed that I could smell burning. I saw no flames, and retired to bed. On the next day, I met my other neighbour – a very practical old gentleman who had built his own house. He told me that during the previous day, he had had to enter my rear garden to extinguish a fire which had been started by the lady, who believed that my garden was infecting hers with pests.

Meanwhile, the grass grew longer. It reached a point where it was so tall that if someone sat down, they became hidden by it. As autumn approached, the tall grass just fell over, and seemed to disappear gradually. It returned without fail every spring, and despite not being mowed, it grew healthily. However, the neighbours were unimpressed by my lawn, the untidiest in Napier Road. I decided that I would have to do something to give the impression that my wild garden was by design, rather than simply the result of neglect. So, what I did was to use the mower to create a sinuous, narrow mowed path that ran along the length of the lawn – I created what might be described as a landscaped lawn. I am not sure that this impressed my neighbours, but I felt that I had ‘done my bit’.

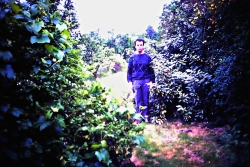

In addition to the lawn, I planted shrubs, which I allowed to grow ‘willy nilly’. My seemingly wild garden was a haven for butterflies. As I walked along the garden, following my sinuous path, clouds of butterflies used to shoot out of the shrubs and other plants. Unwittingly, I had ‘wilded’ or ‘rewilded’ my garden, which in the 1980s and early 1990s was not something that was done. Had I invented what is now known as ‘wilding’, also known as ‘rewilding’? Probably not, but it only began to be adopted as a strategy for reducing loss of biodiversity following work done in the mid-1980s (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rewilding). I must confess that my pioneering rewilding in Gillingham did not result from a desire to save the natural world, nor from laziness, but to save myself from symptoms of allergy.

In the late 1990s, we put the house up for sale. The garden had become such a veritable jungle that our estate agent described it as being “… in a natural state.” Interestingly, the people who bought the house from me liked it because they were looking forward to taming the garden – there is no accounting for taste!