UNLIKE JAIPUR, JODHPUR, and Jaisalmer, the city of Bikaner in Rajasthan is not (yet) overrun with tourists. We have been in Bikaner for three days and apart from at the Junagarh Fort (Bikaner’s most significant historical attraction), we have seen only one European visitor. Bikaner differs from the three Rajasthani cities mentioned in the first sentence in that its streets are not lined with shops designed to attract tourists. Apart from the fort the rest of the city is a fascinating, busy working environment, which someone, like me, who enjoys observing everyday scenes of life in India, has plenty to see.

Many of the older buildings that can be seen in the streets of Bikaner have jharokas – decorative, stone-framed windows that project over the street. They are commonly seen features of the Rajput style of architecture and are still being constructed.

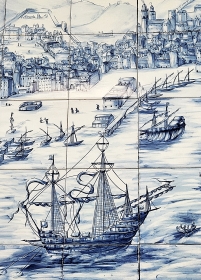

The Junagarh Fort is rich in jharokas. Many of them overlook courtyards within it. One of them is of great interest. From a distance it looked to me like it was decorated with blue and white tiling, like Portuguese azulejo work. Close up, it can be seen to be something else.

A huge consignment of Dutch blue and white Delft ceramic plates had been ordered for the royal family of Bikaner. When that was, I do not know. While they were being transported to India by sea, they were damaged, and arrived broken. Instead of throwing them away, the thrifty maharajah had them cut up to produce tiles, all of which bore details from the pictures that had decorated the plates. The tiles were then used to decorate both the inside and the outside of the jharoka overlooking a courtyard that contains an elaborate water feature: a pool with fountains.

Although there is much more to be seen in the fort, this example of repurposing broken plates intrigued me. The Junagarh Fort is definitely a must-see attraction in Bikaner, but it it is now merely a museum-like remnant of the past. Visitors to the city should see this, but also set aside at least a few hours to absorb the busy atmosphere of enterprise, both traditional and contemporary, in the older districts of Bikaner.