I DO NOT KNOW whether it was deliberate or accidental that currently (until the 7th of April 2024) there are two contrasting (or, maybe, complementary) exhibitions on in the galleries of London’s Tate Britain.

On the first floor, there is an exhibition called “Sargent and Fashion”. It is a collection of paintings by the American-born artist John Singer Sargent (1856-1925), who was born in Florence (Italy) and died in London (UK). The aim of the show is, according to the Tate’s website, to show:

“… how this remarkable painter used fashion to create portraits of the time, which still captivate today.”

The exhibition includes some of Sargent’s portraits alongside a few of the items of clothing that his subjects wore whilst he was creating their portraits. In this well laid out show, the viewer gets to see that Sargent was an excellent painter, whose portraits manage to radiate the natures of the sitters’ personalities. I doubt that most of Sargent’s subjects would have been disappointed with the pictures he produced for them. Many of the paintings are portraits of women. Almost all of them were depicted wearing elegant clothes, and are superbly executed conventional portraits. They celebrate aspects of the ‘respectable’ (i.e., wealthy) society of his times.

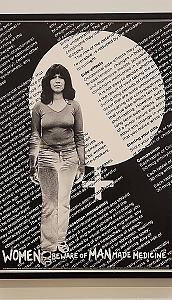

Beneath the Sargent exhibition, on the ground floor of Tate Britain, there is an exhibition showing how women in Britain broke out of their conventional male-dominated lifestyle during the 1970s and 1980s. Called “WOMEN IN REVOLT Art, Activism and the Women’s movement in the UK 1970–1990”, it is according to the Tate’s website, it is:

“… a wide-ranging exploration of feminist art by over 100 women artists working in the UK. It shines a spotlight on how networks of women used radical ideas and rebellious methods to make an invaluable contribution to British culture. Their art helped fuel the women’s liberation movement during a period of significant social, economic and political change.”

During a long part of the period covered by the show, Britain had its first female Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher (in office from 1979-1990). Although she fought her way through hitherto male bastions to emerge as the country’s first lady Prime Minister and showed what women were capable of doing in the world of politics, she was not a feminist icon, as Natasha Walter wrote in The Guardian (online 5th of January 2012):

“Obviously Thatcher was no feminist: she had no interest in social equality, she knew nothing of female solidarity … We should never forget her destructive policies or sanitise her corrosive legacy. But nor should we deny the fact that as the outsider who pushed her way inside, as the woman in a man’s world, she was a towering rebuke to those who believe women are unsuited to the pursuit and enjoyment of power. Girls who grew up when she was running the country were able to imagine leadership as a female quality in a way that girls today struggle to do. And for that reason she is still a figure that feminists would be unwise to dismiss.”

However, as Baroness Burt of Solihull said in the House of Lords on the 5th of February 2018:

“… my next figure is 1979, which, of course, was the date when we got our first female Prime Minister. Personally, I would feel more inclined to celebrate this milestone if she had encouraged other women to come forward, to use some of the talented women that she had at her disposal. But, sadly, she got to the top and pulled the ladder up behind her, which is a great shame, because the whole point of having representation from all parts of society is to make for better government.”

As several exhibits on display at the Tate (until the show ends on the 7th of April 2024), Mrs Thatcher was intensely disliked by artists encouraging ‘female liberation’.

Before entering the exhibition, I was a little worried that all I would see was propaganda and other polemic material. Well, there was plenty of that kind of thing, and much of it was both interesting and often visually intriguing – sometimes quite witty. The exhibition, which is excellently curated, also includes many paintings, sculptures, videos, and other artistic items. These have mostly been created by female artists with whom I am not familiar. And all of them are both visually engaging and satisfying. Several of these were of Indian heritage, and others have ‘black’ African heritage. There are also cases containing printed material that propagated feminist ideas. Included amongst these were a few copies of the magazine Spare Rib, which I remember seeing at friends’ houses many years ago. My future wife was one its readers. Published between 1973 and 1993, its aim was to challenge the traditional roles of females (of all ages) and to explore new ways in which they could engage in society. In fact, this was the aim of many – if not all – of the works in the exhibition.

We visited both exhibitions today (the 28th of February 2024), to experience the contrast between them. Both are excellent in their own ways and achieve what the curators intended. They are both well worth visiting. However, to my taste, the exhibition on the ground floor was far more exhilarating and inspiring, that the more conventional show on the floor above it.