THE WORD ‘INSPIRATION’ has at least two meanings. One of them is ‘to breathe in (i.e., inhale air). When air is inhaled, many of the oxygen molecules it contains are converted to become other substances, some of which is carbon dioxide that is exhaled. Another meaning of the word is to be mentally stimulated, often by something one has perceived in the world around us. What results from this form of inspiration might not much resemble whatever it was that caused it. Today (the 6th of August 2023), we visited a small exhibition in one room of London’s National Gallery. Showing until the 29th of October 2023, the exhibition is called “Paula Rego: Crivelli’s Garden”.

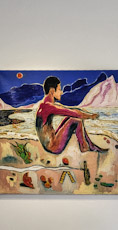

The exhibition contains two major works: “La Madonna della Rondine (The Madonna of the Swallow)” painted in about 1490 by Carlo Crivelli (c1435-1495); and “Crivelli’s Garden” painted in the early 1990s by Paola Rego (1935-2022) when she was the National Gallery’s first Associate Artist between 1990 and 1992. There are also some sketches that Rego made for her enormous painting, originally designed to be a mural.

Both the Crivelli and the Rego paintings are excellent, but quite different in style. However, Rego was inspired to create her mural after seeing Crivelli’s altarpiece. Although both paintings are of religious subjects, there is no obvious similarity between the two of them. As Paola Rego said in 1992:

“If the story is ‘given’ I take liberties with it to make it conform to my own experiences and to be outrageous.”

And that is what she has done after having been inspired by Crivelli’s masterpiece.

The paintings at the base of Crivelli’s altarpiece (the ‘predella’) include scenes set in gardens. According to the National Gallery’s website, what Rego did was to reimagine:

“…Crivelli’s house and garden to explore the narratives of women in biblical history and folklore based on paintings across the collection and stories from the medieval Golden Legend. Her figures inspired by the Virgin Mary, Saint Catherine, Mary Magdalene and Delilah, share the stage with other women from biblical and mythological histories.”

She has populated her picture with portraits of people she knew including (to quote the website again):

“…friends, members of her family and staff at the National Gallery whom she asked to sit for her, including Erika Langmuir, Lizzie Perrotte and Ailsa Bhattacharya who were members of the Education Department at the time.”

The resulting work is both beautiful and fascinating, but quite different from the 15th century work which had inspired her.

Whether your artistic preferences are for art created during the Italian Renaissance or in the late 20th century, this small exhibition will not disappoint you. If you enjoy both, as I do, then this inspiring show of artistic inspiration is a ‘must see’ event.