This extract from “REDISCOVERING ALBANIA” by Adam Yamey describes a part of Albania where much weaponry was manufactured during the Communist era (1944-91).

“We followed the River Osumi upstream [from Berat], passing an isolated working military camp with camouflaged concrete buildings. The road wound up the valley crossing numerous tributaries of the Osumi. Next to many of these small bridges there were construction sites, which were associated with the building of the Trans Adriatic Pipeline. This will carry gas from Kipoi (just east of the Greek city of Alexandropolis) to Seman (a few kilometres north of Vlorë on the Adriatic). From there, it will go under the sea and resurface at the southern Italian coast south east of Lecce. This gas-carrying modern ‘Via Egnatia’ (or maybe it should be called ‘Via Igniter’) will follow the valley of the Osumi, then curve around Berat, before heading westwards towards the sea. It is part of a huge project to transport gas from Azerbaijan to western Europe.

The town of Poliçan was a pleasant surprise. We were expecting to find a drab place because of its industrial heritage. Far from it: Poliçan was a cheerful, vibrant place. We parked at the top end of the sloping triangular piazza named after the large mountain (Tomorr: 2,416 metres), which dominates the area around Berat and Poliçan. The piazza, is a right-angled triangle in plan. Its two shorter sides were lined with well-restored, freshly painted Communist-era buildings with shops and cafés. We joined the crowds drinking under colourful umbrellas outside cafés on the Rruga Miqesia, which runs off the piazza towards the town’s cultural centre and Bashkia (both built in the Communist period). It was about 11 am on a working day. There seemed to be many people with sufficient time for sitting leisurely in cafés or just strolling up and down the street. A girl, who ran a mobile ‘phone shop (on her own), sat with friends at a table in a café near to the shop, and only left them if a customer entered her showroom. A long out of date poster on a building advertised a meeting in Tirana for adherents of the Bektashi sect.

Near the upper end of the triangular piazza, there was a new marble monument commemorating Riza Cerova (1896-1935). He was born just south of Poliçan, and became a leading protagonist in the ‘June Revolution’ of 1924, when supporters of Fan Noli forced Ahmed Zogu to flee from Albania. For a brief time, Noli became Albania’s Prime Minister. However, at the end of 1924, aided by the Yugoslavs and Greeks, Zogu made a counter-coup, and then assumed control the country. Soon after this, he had himself crowned ‘King Zog’. Following Noli’s defeat, Cerova joined the German Communist Party, and later returned to Albania where he led anti-Zogist fighters. He died during an encounter with Zog’s forces.

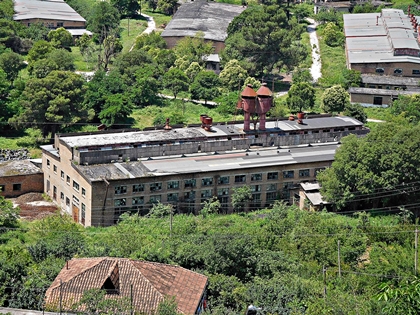

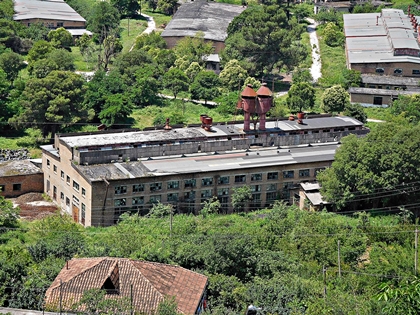

Poliçan was important during the Communist period. It was home to an enormous arms and ammunition factory, the KM Poliçan, which was opened in 1962. This produced its own versions (the ASH-72 and ASH-82 series) of the Kalashnikov gun as well as other munitions. The factory lies amidst cultivated terraced fields on the slopes of a natural amphitheatre away from, and beneath, the southern edge of the town. Workers used to approach the factory from the town by a long staircase. We counted at least twenty-five industrial buildings in the complex, many of them with broken or missing windows. None of the numerous rusting ventilators on these edifices were emitting smoke, and there were no signs of life. The slopes surrounding the factory below were dotted with concrete and metal entrances to underground stores and tunnels. During the unrest of 1997, KM Poliçan was temporarily taken over by criminal gangs while the city was in ‘rebel’ hands. The factory is still used, but mainly to de-activate out-of-date Albanian weaponry. It was difficult to imagine that the peaceful scene, which we observed from a track overlooking it, had such an explosive history.

We travelled southwards through cultivated countryside and past occasional forests, always following the sinuous course of the Osumi. At the edge of Çorovodë, the administrative capital of the Skrapar District, we saw a tourist information poster beside a squat hemispherical Hoxha-era concrete bunker. It portrayed an Ottoman era bridge, which we hoped to see later. In the town’s main square, there was a socialist-realism style monument: a pillar topped by a carved group: one woman with three men. One of them was holding a belt of machine gun ammunition. The base of the monument had ‘1942’ carved in large numerals. On the 5th of September 1942, Skrapar became the first district in Albania to be liberated from the occupying fascist forces. There was a bronze statue of Rizo Cerova in a small park next to the square. Elegantly dressed in a jacket with waistcoat, he is shown holding a rifle in his left hand. His face looked left but his tie was depicted as if it were being swept by wind over his right shoulder.

We ate a satisfying lunch in a large restaurant next to the park, the Hotel Osumi. It backed onto a fast-flowing tributary of the Osumi. After eating, we entered a café a little way upstream to ask for directions to the Ottoman bridge that we had seen on the tourist poster. We were surprised to discover a ‘black’ man at a table, chatting with several Albanians. He spoke perfect English, which was not surprising because he was born in Tennessee (USA). He was teaching English in Çorovodë under the auspices of the Peace Corps. With pencil and paper to hand, he was compiling his own map of the town. When we told his companions that we were trying to find the old bridge, they advised us that it was only accessible with a rugged four-wheel drive vehicle.

Driving further southwards, we reached the spectacular Canyon of the Osumi (Kanioni i Osumit, in Albanian). It is about twenty-six kilometres long, deep, and narrow. At places where the road came close to the edge of the canyon, we obtained good views. From above, it looked as if the cultivated rolling fields and pastureland had been cracked open. The crack’s walls were steep sided, with dramatic striations of whitish rock. Far beneath us at the bottom of this fissure, the River Osumi flowed around its many bends. Standing at the canyon’s precipitous edge, we could only hear birdsong and water rustling over the river’s stony bed far below us.

Retracing our steps to Berat, we passed an abandoned building with a fading circular coloured sign painted on it. It depicted a grey cow standing between a woman in a white dress, who was writing on a clipboard, and a man in a white coat such as doctors wear. In the background, a man in an overcoat holding a shepherd’s crook, was leading a flock of sheep towards the grey animal and its attendants. Around the edge of the picture, we read the words ‘Stacioni Zooteknise’, which literally translates as ‘zoo technical station’. The building with its peeling plaster and patches of exposed brickwork had once been an animal husbandry centre.”

Adam Yamey’s book REDISCOVERING ALBANIA is available from Amazon, bookdepository.com, lulu.com, and is on Kindle

40.606103

20.100056