MR HUSSAIN WAS a charming old gentleman full of ‘joie de vivre’, even when infirmity confined him to his bed. A retired businessman, we knew him as ‘Mahomet Uncle’. He was a Kutchi Memon (a Muslim whose ancestors had migrated from Kutch – now a part of Gujarat – to Karnataka). He was immensely popular. His many friends and relatives used to visit him to enjoy his company and to share their news. Once, near the end of his life, we went to his house to wish him ‘Eid Mubarak’ at the end of Ramazan. While we were in his bedroom, where he used to ‘hold court’, a seemingly endless stream of people passed through his front door to celebrate the occasion with him. His death was a great loss not only to his family but also to a vast number of people in Bangalore, who knew and loved him.

We were introduced to Mahomet Uncle by one of his sons who was studying in London at the same time as my then future wife, Lopa, and I were undertaking post-graduate courses. Mahomet Uncle lived in a house on Aly Asker Road Cross, a quiet lane close to the busy Cunningham Road. The Cross road is an offshoot of the larger Aly Asker Road. We have often travelled along this thoroughfare, not only to visit Mahomet Uncle but also other friends who live close by. In addition, when returning from the excellent Shezan Restaurant (on Cunningham Road) to the Bangalore Club, where we often stay, the best route is along Aly Asker Road.

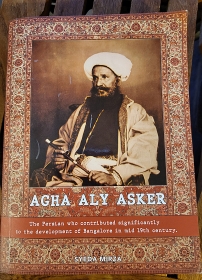

For many years, I have wondered about Aly Asker and why a road should have been given his name. The answer was provided only recently, at the end of January 2024 just before we flew from Bangalore back to London. My friend Subhash Agarwal, with whom I often enjoy an afternoon cup of tea on the lawn in front of the main building of the Bangalore Club, knowing of my interest in the history of Bangalore, kindly presented me with a book, which has the title “Agha Aly Asker”. Published in 2019, it was written by Syeda Mirza, the wife of Aly Asker’s great grandson. The book is well-researched and a pleasant, compelling read. Apart from detailing his life, the author gives many insights into the traditional Persian ways of life.

Aly Asker, a Persian, was born in Shiraz (Persia) in 1808. In 1824, along with his two brothers, he set off for India to sell horses to the British military. They travelled with 200 horses by sea to Mangalore, and then travelled overland to Bangalore. The brothers left him and the horses in Bangalore, where he began selling them to the army of the East India Company. The business was successful, and he imported more batches of horses to sell. Ali Asker became a successful businessman and was befriended by Sir Mark Cubbon (1775-1861), who was the Chief Commissioner of Mysore between 1834 and 1861. Amongst Cubbon’s many achievements were the introduction of Kannada and Marathi as the official state languages, instead of the formerly used Urdu, Hindi, and Persian.

Cubbon was very fond of horses, and is said to have had up to 60 in his stables. His equestrian interests helped develop his friendship with Aly Asker. As a result, Cubbon asked Aly Asker, who had already built himself a fine bungalow, to build 100 bungalows to accommodate the growing military establishment that was developing in Bangalore. Cubbon offered the land free of charge, but Aly Asker told him that he was happy to pay for it, which he did. The residences were constructed on land near today’s Palace Road, Sankey Road, Cunningham Road, and Richmond Road. Many of these houses no longer exist – Bangalorean property developers seem to value heritage far less than profit. One notable example that still stands is the Balabrooie State Guest House. Aly Asker also owned the land on which the luxurious Windsor Manor Hotel now stands.

Aly Asker’s interest in horses extended beyond trading, He was keen on horse-racing, and is said to have been important in putting Bangalore on the horse-racing map of India. His biographer, Syeda Mirza, includes an appendix in which the many victories of Aly Asker’s horses are listed. He was a frequent visitor to the racetrack in Bombay, and then later in Bangalore.

It was their interest in horses that drew together Aly Asker and another noteworthy person in Mysore State – Mummadi Krishnaraja Wodeyar III (1794-1868), the 22nd Maharajah of Mysore. It was through Aly Asker’s help that the British were encouraged to allow the Maharajah’s adopted son Chamarajendra Wadiyar X (1863 – 1894) to become his successor on the throne. Initially, the British, who effectively ruled the state, were reluctant to recognise him as the successor, and it was partly due to the gifts that Aly Asker chose for Queen Victoria that changed their mind in his favour.

Aly Asker died in Bangalore in 1891. He is buried in a cemetery near to the city’s Hosur Road. This is a Persian Cemetery that stands on land granted to Aly Asker and his heirs in 1865. His simple grave is beside that of his wife, and is shown in in a photograph in Mrs Mirza’s book. She noted that he established Bangalore’s first Shia Muslim community. It was when he married Sheher Bano that the first Muharram rituals were first observed in the city. In his will, Aly Asker left money to build the Masjid-e-Askari. It was built in 1909, and still remains as the city’s oldest Shia mosque.

So, having read Syeda Mirza’s book, I now know why there are roads in Bangalore named after Aly Asker. In addition to detailing his life in, and contributions to, the development of Bangalore, Mrs Mirza also described the exciting journey that Aly Asker made between his native land and India. Oddly, Aly Asker does not appear in the index of the authoritative history of Bangalore. “Bangalore Through The Centuries” by M Fazlul Hasan (publ. 1970). In a later (2014) comprehensive history of the city, Maya Jayapal makes one mention of Aly Asker Road, but gives no description of Aly Asker’s contribution to the story of Bangalore. It is therefore valuable that Syeda Mirza took the trouble to write about Aly Askar. As her book bears no ISBN number, and I could not find it either on Amazon or the much wider ranging bookfinder.com, it might well have been privately published, and is now probably quite a rare volume. I am very grateful to Subhash Agarwal for gifting me this informative book – a window on a hitherto poorly described aspect of Bangalore’s history.