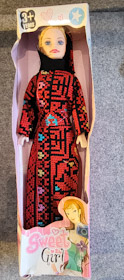

THERE IS A SUPERB exhibition at Cambridge’s Kettles Yard until the end of October 2023. The beautiful exhibits are mainly garments embroidered by Palestinian women before and after 1947. There are also a few other items including Palestinian propaganda posters depicting women wearing embroidered garments. The labels next to the exhibits are full of interesting information. Several of the topics particularly interested me.

Some of the garments were made using scraps of pre-used materials – for example bits of old clothes or even sacking and other packing materials. These old textiles were stitched together to create new clothes. This reminded me of a similar recycling of old materials which I saw at an exhibition of Japanese recycling at London’s Brunei Gallery.

I saw examples of Palestinian dresses which seemed very long. The length of these skirts was for a purpose. The cloth could be raised up to produce pocket like folds in which objects could be carried. These dresses were worn by Bedouins living in the Bethlehem and Jerusalem areas.

There was a widow’s dress. It was dark blue – the colour signifying grieving – and trimmed with red threads, which signified that the wearer was ready to be remarried.

One room was dedicated to embroidery and how the troubled situation in Palestine affected it. In refugee camps, some of the traditional materials were unavailable, and women had to embroider using whatever threads they could get hold of. There were several embroidered dresses adorned with decorations including the Palestinian flag and other patriotic motifs. These were displayed in the same room as the pro-Palestine propaganda posters that show women wearing embroidered garments.

I hope that what I have written gives you something of the flavour of this fascinating exhibition. Despite the intense reactions that discussing the plight of the Palestinians often arouses, the exhibition at Kettles Yard takes a reasonably balanced view of the situation. Its emphasis is on the skills of the Palestinian embroiderers rather than the politics of the part of the world where some of them still reside.

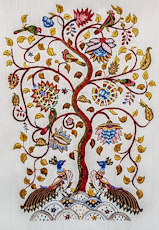

PONDICHERRY IS RICH in wonderful attractions, many of them souvenirs of its French colonial past. One of the most delightful of these is the Cluny Embroidery Centre on Rue Romain Rolland, a street named after a French writer and Nobel Prize winner who met Gandhi and was sympathetic to India and its philosophies.The Embroidery Centre is housed in an 18th century French Colonial building (a former residence, which was built by 1774) that forms part of a religious centre under the aegis of the Order of Cluny. It is believed that one of the former owners of the house donated it to help poor women in need. This must have been before 1829, when the Embroidery Centre was established. Every day except Monday and Sunday, at least twenty women of various ages arrive at the centre and take their places at tables in a large room with tall windows that open out into a verandah supported by neoclassical pillars and decorated with elaborate stucco bas-reliefs. The verandah looks out onto a courtyard surrounded on three sides by other buildings, parts of the convent, and the outer wall with a decorative entrance gate.This ensemble of buildings forms only part of a much larger complex of buildings, some of which surround another courtyard filled with a garden.After singing what sounds like a hymn, the women begin working on their elaborate embroideries. They stitch according to patterns designed by artists who work at the centre. While they work away silently with needle and thread, a simple sound system provides background music at a low volume.Dressed in white habit, Sister Agatha, who runs the convent, watches over the ladies at work and organises the sales of their labours to visitors who step into this peaceful sanctuary a few feet away from the noisy outside world.The resulting products are exquisitely beautiful. They embroider everything from coasters to handkerchiefs to napkins to pillowcases to table cloths and bedcovers. Visitors to the centre can purchase these treasures of fine needlework. Or, customers can place orders for specific items they need. The women who embroider at the centre get paid on a piecework basis. Some of them have had a history of mistreatment before joining the centre. Visiting the Cluny Embroidery Centre is a moving experience. It provides a very good example of how a religious order can work for the benefit of the ‘common’ folk.

PONDICHERRY IS RICH in wonderful attractions, many of them souvenirs of its French colonial past. One of the most delightful of these is the Cluny Embroidery Centre on Rue Romain Rolland, a street named after a French writer and Nobel Prize winner who met Gandhi and was sympathetic to India and its philosophies.The Embroidery Centre is housed in an 18th century French Colonial building (a former residence, which was built by 1774) that forms part of a religious centre under the aegis of the Order of Cluny. It is believed that one of the former owners of the house donated it to help poor women in need. This must have been before 1829, when the Embroidery Centre was established. Every day except Monday and Sunday, at least twenty women of various ages arrive at the centre and take their places at tables in a large room with tall windows that open out into a verandah supported by neoclassical pillars and decorated with elaborate stucco bas-reliefs. The verandah looks out onto a courtyard surrounded on three sides by other buildings, parts of the convent, and the outer wall with a decorative entrance gate.This ensemble of buildings forms only part of a much larger complex of buildings, some of which surround another courtyard filled with a garden.After singing what sounds like a hymn, the women begin working on their elaborate embroideries. They stitch according to patterns designed by artists who work at the centre. While they work away silently with needle and thread, a simple sound system provides background music at a low volume.Dressed in white habit, Sister Agatha, who runs the convent, watches over the ladies at work and organises the sales of their labours to visitors who step into this peaceful sanctuary a few feet away from the noisy outside world.The resulting products are exquisitely beautiful. They embroider everything from coasters to handkerchiefs to napkins to pillowcases to table cloths and bedcovers. Visitors to the centre can purchase these treasures of fine needlework. Or, customers can place orders for specific items they need. The women who embroider at the centre get paid on a piecework basis. Some of them have had a history of mistreatment before joining the centre. Visiting the Cluny Embroidery Centre is a moving experience. It provides a very good example of how a religious order can work for the benefit of the ‘common’ folk.