Between 1944 and 1991, Albania was ruled by a Stalinist dictatorship under the leadership of Enver Hoxha until his death in 1985, and then under Ramiz Alia. The country was even more isolated from the rest of the world than North Korea is today. It was impossible for individuals to visit the country unless they were members of a tour group. In May 1984, I joined one of these groups and spent a most interesting fortnight in the country. Our hosts, the state-run Albturist company, made sure that we had little or no contact with Albanians other than our tour guides and driver, who was a trusted Communist party member. Our hosts hoped that we would only see what the authorities wanted us to see. Their aim was to make us come away from Albania feeling that its repressive regime was one to be admired. I was the only dentist in our group. I managed to gain a tiny insight into the state of dentistry in Albania. The following extracts from my book “Albania on my Mind” reveal something of what I learned. ‘Aferdita’ and ‘Eduard’, mentioned below, were our Albanian tour guides. Although their job included keeping us ‘under control’ and away from other Albanians, they were curious about the world beyond Albania’a watertight borders.

Our tour began in the northern city of Shkodër.

“Our coach headed out of Shkodër along the main road leading southwards. Once we were out of town, Aferdita delivered the first of her brief daily lectures. Every day, she treated us to a discourse on one of a variety of different aspects of life in Albania. The one that I can recall best was on the subject of medicine. She informed us, whilst we were travelling towards Sarandë some days well into our tour, that since the advent of the communists not only had malaria been eradicated, but also tuberculosis and syphilis. After extolling the virtues of her country’s medical facilities, she offered to answer any questions that had arisen in our minds as a result of her lecture. No one said anything. Then, Julian, our British chaperone, knowing already that the young lady doctor travelling with us was a reticent person, asked me, the dentist on board, to pose a question. I asked whether antibiotics were readily available in Albania. My reason for asking this was that I believed that the country, which was clearly trying to be totally self-reliant, would have been reluctant to import costly pharmaceuticals. Aferdita replied indignantly: “Why, of course they are.”

And then, spreading her hands wide apart, she exclaimed:

“When we reach the next town, I will get you a packet of antibiotics this large.”

Sadly, she never fulfilled this unusually generous offer.”

Flash flood in Shkodër, 1984

“After an unexceptional lunch, I roamed around the streets of Shkodër. I came across a small public garden, which was dominated by a chunky statue of Joseph Stalin. Even 30 years after his death, Albania continued to honour him. It was the only country in Europe still revering that illustrious Georgian. There was even a town, Qyteti Stalin (now known by its pre-Communist name as ‘Kuçovë’), named in his memory, but we did not visit it. I am pleased that I saw this statue, because although I did see many other statues on our trip, they were mostly depictions of Enver Hoxha.

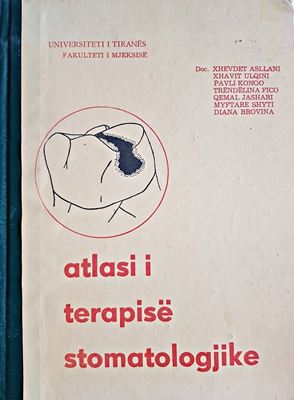

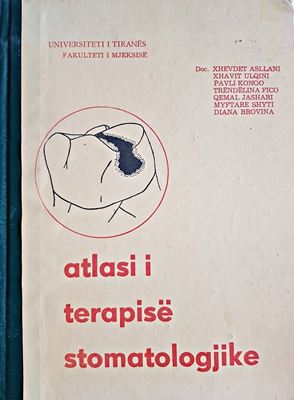

I discovered a bookshop near to Stalin’s monument, and being addicted to such establishments, I entered. I was surprised to find an Albanian textbook of dentistry prominently displayed there. Though crudely illustrated with line-drawings, I could make out that it was quite up-to-date. To the evident surprise of the shop’s staff, I purchased it and another dental book. I still treasure these two unusual souvenirs from Shkodër.”

Backstreet in Gjirokastër

Later during our tour, we visited the historic city of Gjirokastër. Its hotel, like others in Albania, was equipped with a night club, where we, the foreign guests, were entertained by musical ensembles in splendid isolation: no Albanians apart from our guides and a waiter were permitted to enter the club. Incidentally, wherever our group ate in Albania, we were isolated by screens or curtains from other (i.e. Albanian) diners. I later learnt that this was because in 1984 there were great food shortages in the country. We were well-fed, but it was important that Albanians were not able to see that.

“That evening after dinner, a number of us sat with Aferdita and Eduart in the hotel’s night club. Each of the hotels in which we stayed had one of these. With the exception of our two guides and the musicians who performed in them, these clubs were out of bounds for Albanians. This evening we were entertained by a small band that played western pop music, mainly tunes originally performed by the Beatles. The noisy background of these clubs provided our two young guides with opportunities to ask us about life beyond their country’s tightly sealed borders. However, it was clear that Aferdita was trying to eavesdrop on Eduart and vice-versa. As the musicians strummed away in the semi-gloom of the club in Gjirokastër, Aferdita turned to me, rolled her lower lip away from her teeth, and asked my opinion of her gums. She wanted to know if they had been treated properly. I told her that I was unable to give her an opinion in such poor light.

The following morning, I spotted some tubes of Albanian toothpaste on display in a locked glass display case near the hotel’s main entrance. I tried to communicate to the receptionist (who did not understand English) that I wished to purchase a tube. I used to collect toothpastes from wherever I travelled and was curious to taste its contents. Whilst I was doing this, Aferdita appeared, and asked me what I wanted. I told her. She explained my desire to the receptionist, and moments later I had become the proud owner of a tube of Albanian dentifrice.”

Many years later…

“In 2001, long after my trip to Albania, I began working in a dental practice in west London. Many of my patients were, and still are, refugees from the places in the world, which are stricken by military and political conflicts. Algerians, Iraqis, Afghans, Kurds, Palestinians, Eritreans, and many other others who have fled their far-off disturbed homes sit in my surgery and reveal the ravages that life has inflicted on their teeth. During the terrible conflicts in the former Yugoslavia, many of my patients hailed from Kosovo, and usually spoke poor English in addition to their native Albanian. Many were the smiles that I elicited from them when I quoted the old party slogans, undoubtedly poorly pronounced, and wished them ‘Mir u pafshim’ instead of ‘Goodbye’ at the end of their appointments.”

“ALBANIA ON MY MIND” by Adam YAMEY may be purchased from Amazon, lulu.com, bookdepository.com, your bookshop. It is also available as a Kindle

41.153332

20.168331