THE AUCTION HOUSE Christies was founded in London in 1766 by James Christie (1730-1803). Their main premises are on King Street, near St James Palace in the City of Westminster. Usually, the auction house is open to the public, who may enter and view the items waiting to be auctioned, and to watch or participate in an auction. Until 12 March 2026, works from the collection of the Belgian couple Roger and Josette Vanthournout, both now deceased, are up for sale. The sale is being held as a series of auctions over a period that extended from 25 February 2026 until 12 March 2026.

The Vanthournout couple have been collecting art for over 60 years. At first, they collected Chinese vases, but soon after that, they began buying modern and contemporary art. Roger trained as an interior designer and ran a furniture store in Izegem, Aurora, which had been founded by his father in 1921. Josette (née T’Kint) was an artist and an art lover. From the 1950s onwards, the couple travelled a great deal, visiting art fairs where they engaged directly with artists, dealers and galleries. They tended to buy much of their art from artists, who had not yet achieved great fame, and by doing so acquired artworks at reasonable prices. And viewing the pieces on display at Christies today (5 March 2026), one can easily see that Roger and Josette both had a ‘good eye’, and bought wisely. After the widowed Josette died in 2025 aged 95, the family decided to sell the collection.

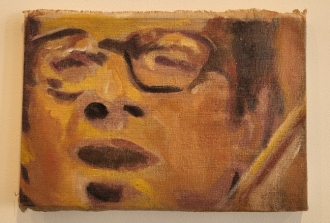

And what a collection it must have been, judging by what we saw on display at Christies. There were fine examples of artworks by, to name BUT A FEW: Josef Albers, Pablo Picasso, Man Ray, Rene Magritte, Henry Moore, Yayoi Kusama, Jean Arp, Lucio Fontana, Jean Dubuffet, Lynn Chadwick, Paul Delvaux, Jacques Lipchitz, Tracey Emin, and James Ensor. I was interested to see a couple of works by Victor Vasarely (1906-1997) because when I lived at home, we had one of his abstract prints hanging on the wall of our living room (I have not seen the print since 1991). There were several sculptures by Antony Gormley. These are quite unlike any of the many works I have seen by this artist. Josette and Roger were lucky to have these examples of his work.

The collection we saw at Christies was well-displayed and filled with an amazing array of art created in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Once they have been auctioned, many of the bought by private collectors and galleries far away from London, it will be a very long time, if ever, before they can be seen again by the London public.

Because it is possible to see works of art that are not usually on public display, visiting Christies (and other auction houses) allows ‘the man (or woman) in the street’ to catch a glimpse of artists’ creations that are frequently not usually accessible except by their owners. And even if you have no intention of making a bid, the staff at Christies are most welcoming and willing to answer any questions you might have regarding the items awaiting auction.