SOME PEOPLE SAY “save the best till last”. This is what we did accidentally while spending several days exploring the 2025/26 Kochi Muziris art biennale. Much of what we saw at this biennale was far inferior to what we had seen when visiting the four previous biennales. Most of this biennale’s offerings were rich in messaging but insubstantial artistically. The exception to this sad situation is an exhibition held at the Durbar Hall, which is across the sea from Fort Kochi in the city of Ernakulam.

The exhibition at Ernakulam is a large collection of (mostly) paintings by Gulam Mohammed Sheikh, who was born in 1937 in what is now Gujarat. His artistic training took place first at the MS University in Vadodara, then at London’s Royal College of Art.

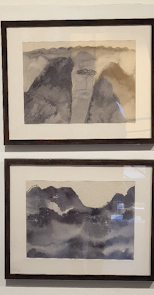

The exhibition includes works from the various stages of his career from the 1960s until today. Sheikh’s work provides imaginative, creative, original, beautifully executed, refreshing views and interpretations of the world and its inhabitants.

Amongst the many superb creations on display, there is a series of Mappa Mundi paintings, in which, to quote Wikipedia, Sheikh:

“… defines new horizons and ponders over to locate himself in. Sheikh construes these personal universes enthused from the miniature shrines where he urges the audience to exercise the freedom to build up their Mappa Mundi.”

These wonderful artworks that were inspired by mediaeval maps of the world provide the viewer with exciting expressions of Sheikh’s interpretations of the world, past and present, real and imagined. In one room at Durbar Hall, there is a wonderful film that, in a way, brings Sheikh’s Mappa Mundi to life.

Each of Sheikh’s artworks tells a story. However that story is open to each viewer’s own interpretation. The artist’s works are not only vehicles for a story or stories, but they are also aesthetically sophisticated: art at its best.

It was a great pleasure to see Sheikh’s art. Unlike much of the other exhibits in the Biennale, his work does not rely on gimmickry, sound effects, lighting effects, film clips, ‘objets trouvés’, and explanatory notes. Sheikh’s works are the products of a technically competent painter who is able to express his imaginative ideas in ways that are both aesthetically pleasing and highly original.

Seeing the exhibition of Sheikh’s works has revived my enthusiasm for art, which had begun to flag while visiting a seemingly never ending series of mediocre artefacts being displayed at the various sites of the 2025/26 Kochi Muziris Biennale.