JUST OVER FIVE thousand feet above sea level, the small town of Munnar, watered by three streams that meet in the town’s centre, is perched on the slopes of the hills that surround it. Unlike many places we have visited in India that are rich in historical monuments and artistic delights, the joy of Munnar is its situation and the beautiful views of the hills and tea gardens that surround it. Having said that, we did visit a couple of old buildings – old by Munnar’s standards (the town did not exist before the nineteenth century) – during our morning stroll on 14 January 2026.

Walking down the steep road from our hotel to the bazaar area near where three rivers meet, we passed sellers of long sticks of sugar cane topped with green leaves. The canes were stacked vertically creating what resembled a curtain of bamboo stalks. Facing the canes was a long line of parked Mahindra jeeps, all waiting to be hired. As we passed their drivers, we were asked whether we needed a taxi.

The busy bazaar area of Munnar resembles that found in many small towns in India. The streets that wound their way through this area have a never-ending stream of traffic: autorickshaws, trucks, cars, minibuses carrying visitors, large buses, and motorised two-wheelers. Bridges cross the river to join two equally bustling shopping areas.

Near the point where the three rivers meet, there is a bank where we got some cash: many businesses, including hotels and some restaurants require cash payments or electronic payments, which we cannot do. After dealing with the bank, we sampled a couple of types of locally grown tea: cardamom and masala milk teas.

After quenching our thirst, we headed away from town along the road that leads to Ernakulam. This leafy thoroughfare is lined on one side with market stalls, selling mainly ‘homemade’ Munnar chocolate and outdoor clothing (anoraks, hats, etc).

After walking up a gradual incline for about 300 yards, we passed the Government Anglo Tamil Primary School (‘GATP’) and Model Pre-Primary. The GATP was founded in 1918, and its building with corrugated iron roofs and Tamil style pillars looks quite old.

Not far from the school and high above it is an even older edifice. Completed and consecrated in 1911, this is the Church of South India’s Christ Church. Built in a gothic style using local granite blocks, it is a grey coloured building, which, to my taste, is not particularly attractive.

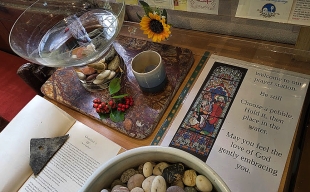

Inside, this small church with its timber beamed roof has its own charm. Even though it was long after Twelfth Night the church was gloriously colourful with its Christmas decorations still in place. A service was in progress. The number of people attending was under twenty.

The church has a few stained glass windows and several plaques commemorating Brits who were associated with Munnar. One white marble memorial commemorates Archibald William Lunel Vernede who died in Munnar in 1917, aged 67. For many years, he had been: “Superintendent and District Magistrate of the Cardamom Hills”. These Hills are the part of the Western Ghats that includes Munnar.

Another memorial recalls a more recent death. That of Cecil Philip Gouldsbury, who was a tea planter in the High Range (near Munnar), and died in 1971. I did a little research, and found that Cecil was born in Calcutta in 1886, and died in Wiltshire (UK).

Although not a great beauty, Christ Church is a functioning Church, one of the oldest surviving buildings in Munnar, and a place that evokes the colonial era in the town.

After our pleasant stroll during which we enjoyed seeing the varying verdant vistas, we rode back to our hotel in an autorickshaw.

[And now a minor gripe. In India, the three-wheeler cabs used to be, and are still often called ‘autorickshaws’. However, their drivers, seeing a European face, will refer to them as ‘tuk tuks’, the name by which they are known further east ( e.g. in Thailand). I prefer to call these vehicles autorickshaws, as I have been doing over more than 30 years of visiting India.]