IN WARWICK, I chanced upon a fascinating book in a charity shop. It is Part 2 of “Stanley Gibbons Priced Catalogue of Stamps of Foreign Countries 1912”. When it was published, it could be purchased for as little as half a crown (2/6, which is 12.5 pence). I paid a lot more for it, but not an excessive amount.

I felt compelled to buy it because of its date and my interest in Albania. For, on the 28th of November 1912, the independence of Albania was proclaimed in the seaside town of Vlorë. Albania’s independence was formally recognised when the Treaty of London was signed in July 1913. The catalogue I bought in Warwick was published some time in 1912 and most likely before independence was proclaimed. As far as the publishers and the compilers were concerned, what is now Albania was still part of the Ottoman Empire.

The index of the catalogue contains an entry for “Albania (Italian P.O.)”. This needs some explanation. Throughout the Ottoman Empire, there were postal services operated by foreign (i.e., not Ottoman) countries. A website (www.levantineheritage.com/foreign-post-offices.html) reveals:

“In the 18th century, foreign countries maintained courier services through their official missions in the Empire, to permit transportation of mail between those countries and Constantinople [sic] the Empire capital. Nine countries had negotiated Capitulations or treaties with the Ottomans, which granted various extraterritorial rights in exchange for trade opportunities. Such agreements permitted Russia (1720 & 1783), Austria (1739), France (1812), Great Britain (1832) and Greece (1834), as well as Germany, Italy, Poland, and Romania, to maintain post offices in the Ottoman Empire. Some of these developed into public mail services, used to transmit mail to Europe. The Ottoman Empire itself did not maintain a regular public mail service until 1840, when a service was established between Constantinople and other major cities in the country and this was slow to develop and expand. The gap in this capacity was very much filled with the various foreign post offices which continued functioning right till the beginning of WWI in 1914 …”

Hence, the entry in the catalogue’s table of contents. I turned to the page listed and found the section on Albania. The Italian Post Offices in the Turkish (Ottoman) Empire issued stamps, to quote the catalogue, which:

“…surcharged or over-printed for use in Italian post offices abroad.”

These stamps were the regular issues but, to quote the catalogue:

“… distinguished by the removal of some details of the design, over-printed with Type…”

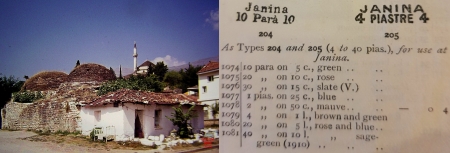

Different Italian stamps were overprinted with names of places and a Type number. For example, Italian stamps were over-printed with: “ALBANIA. 10 Para 10. 201” (where ‘10 Para’ is a monetary denomination and ‘201’ is the Type number), or “Durazzo. 4 PIASTRE 4. 205”, or “Valona, or other place names. 10 Para 10. 208”. Durazzo and Valona being the Italian for the Albanian names Durres and Vlore.

Within the Albanian section of the catalogue there is also an illustration of the over-printing “JANINA. 4 Piastre 4. 205”. Janina is the name of a town now in Greece, Ioannina (Ιωάννινα). In 1912, this town was not in what was then Greece, but in the Pashalik of Janina, part of the Turkish Empire. In February 1913, following the battle of Bizani in the First Balkan War, the town was absorbed into Greece. Many Albanians still consider that by rights Ioannina should be a part of a Greater Albania. The large Albanian population in the town was forcibly reduced by population exchanges in the early 1920s and also the pre-WW2 Greek government’s policy of strongly encouraging people of Albanian ethnicity to regard themselves as Greeks. When I visited Ioannina in the 1970s, there were the remains of Turkish buildings but many of them were in a sad condition. I do not know whether they have been restored since then.

My purchase in Warwick has proved to be of interest. It records the state of postage stamps on the eve of great changes that were about to happen in the Balkan peninsular as well as illustrating aspects of European colonialism, both political and economic.