MOUNT STREET GARDENS in London’s Mayfair was formerly the burial ground of St George’s Church in Hanover Square. Its name derives from Mount Field, where there had been some fortifications during the English Civil War. The burial ground was closed in 1854 for reasons of protecting public health. St George’s Church moved its burials to a location on Bayswater Road, St Georges Fields, which is described in my book “Beyond Marylebone and Mayfair: Exploring West London”. In 1889-90, part of the land in which the former burial garden was located became developed as the slender park known as Mount Street Gardens (‘MSG’- not to be confused with a certain food additive). Small as it is and almost entirely enclosed by nearby buildings, it is a lovely, peaceful open space with plenty of trees and other plants.

The garden is literally filled with wooden benches. Unlike in other London parks where there is often plenty of space between neighbouring benches, there are no gaps more than a few inches between the neighbouring benches in MSG. The ends of neighbouring benches almost touch each other. The result is that MSG contains an enormous number of benches given its small area. And they are much appreciated by the people who come into the park and rest upon them.

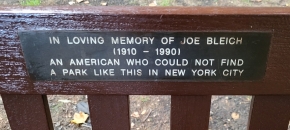

Each bench bears a memorial plaque. Many of these memorials commemorate people from the USA, who have enjoyed experiencing the MSG. And most of these having touching messages written on them. Here are just a few examples: “For my children Philippa and Richard, young Americans who may one day come to know this place. Richard L Feigen. 8th August 1987”; “Seymour Augenbraun – a New Yorker and artist for whom this spot in London is his oasis of beauty. From his wife Arlene and family on July 15th 1986”; “To honour a dear brother and sister Ira and Nancy Koger of Jacksonville Florida”; “This seat was given by Leonora Hornblow, an American, who loves this quiet garden”; “In memory of Frances Reiley Bochroch, a Philadelphia lady who found these gardens a pleasant pace”; and “In loving memory of Joe Bleich (1910-1990). An American who could not find a park like this in New York City,”

There are plenty of other similar memorials to Americans on the benches. All of them interested me, but one of them particularly stood out: “To commemorate Alfred Clark, pioneer of the development of the gramophone. A friend of Britain, who lived in Mount Street”. Clark (1873-1950) was a pioneer in both cinematography and sound recording. Eventually, he became Chairman of EMI. A keen collector of antique ceramics, he donated some of his pieces to London’s British Museum.

Not all of the benches are memorials to Americans. There are others to Brits and people from other countries, but the Americans outnumber the rest. Had it not been for the extraordinarily large number of benches in this tiny gem of a park, I doubt that my eye would have been drawn to the commemorative plaques, but having seen the one in memory of Joe Bleich, who was unable to find a park like it in NYC, I was drawn to examine many of the others.