WHAT IS YOUR EARLIEST memory of a news item? In my case, I remember my parents discussing something about Cuba. This was The Cuban Missile Crisis of October 1962. I had little or no idea about it, but later I learned that US President John F Kennedy was involved in its resolution. A year later, when we were staying in the USA, we were there when he was assassinated. I well recall that and my feelings about it at the time. That remains in the forefront of my memory, but far back in the fleshy recesses of my grey matter, the name Grunwick resides. While visiting an exhibition at the Tate Britain recently, I saw several photographs that brought this vague memory back into my consciousness.

Grunwick Film Processing Laboratories (‘Grunwick’), located at Willesden in northwest London, processed photographic films and produced finished prints from them. Photographers (mostly amateurs) put their undeveloped exposed films into an envelope along with payment, and sent them to Grunwick, who later returned the developed film and the prints made from it. In 1973, some workers at Grunwick joined a trade union and were subsequently laid-off by the company. The company employed many workers of Asian heritage – including a substantial number of ladies. As the then Labour politician Shirley Williams pointed out, the Asian ladies were being paid very much less than the average wage, and conditions were bad – hours were long, overtime was compulsory (and often required without the employer giving prior notice).

On the 20th of August 1976, Grunwick sacked Devshi Bhudia for working too slowly. That day, three other workers walked out in support of Devshi. Just before 7 pm that day, Jayaben Desai (1933-2010) began walking out of the factory. As she was doing so, she was called into the office and dismissed for leaving early. When she was in the office, Jayaben said (see guardian.com, 20th of January 2010):

“What you are running here is not a factory, it is a zoo. In a zoo, there are many types of animals. Some are monkeys who dance on your fingertips, others are lions who can bite your head off. We are those lions, Mr Manager.”

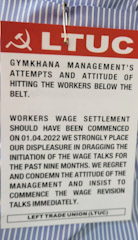

Thus began a two-year long strike, which was supported not only by the company’s workers but also by many politicians and trade unions, including, for a short time, the Union of Post Office Workers, who refused to cross the Grunswick picket lines.

Jayaben was born in Dharmaj, now in the Anand district of the Indian state of Gujarat. Soon after marrying, she and her husband migrated to what is now Tanzania. Just before the Commonwealth Immigrants Act (1968) made it difficult for Commonwealth citizens to settle in the UK, the couple moved to England. There, she was obliged to take up poorly paid work, first as a sewing machinist, and then as a worker at Grunwick.

Not only did Jayaben initiate the strike, but she helped keep it going until the dispute was resolved. In November 1976, when the Post Office workers stopped supporting the strike, she told an assembly of Grunwick’s workers:

“We must not give up. Would Gandhi give up? Never!”

Later, like Gandhi, she employed his tactic – the hunger strike – outside the Trade Union Congress in November 1977. During the court of enquiry led by Lord Justice Scarman, she gave powerful evidence against her erstwhile employer. When the strike was over, she went back to sewing, and then later became a teacher of sewing at Harrow College. After passing her driving test at the age of 60, she encouraged other women to do so to increase their freedom. After her death, some of her ashes were deposited in the Thames, and the rest in the Ganges.

The reason that Grunwick came to mind at Tate Britain was that its current exhibition “Women in Revolt! Art and Activism in the UK 1970-1990” (ends 7th of April 2024) includes several photographs taken at Grunwick during the strike. Three of them include portraits of Jayaben in action.

As I wrote earlier, I had heard of Grunwick, but I could not recall why until I saw the exhibition. As for the remarkable Jayaben Desai, I am happy that I have become aware of her and her amazing achievements.