THE FIRST TIME I visited Turkey was in about 1960. My father was participating in a conference organised by the Eczacibaşi Foundation. It was held in the then luxurious Çinar Hotel on the European shore of the Marmara Sea at a place called Yesilköy, which is about 9 miles west of old Istanbul. This April (2024), we visited Yesilköy both for old times sake and because we had read that the place has several interesting sights to be seen. Incidentally, it was in Yesilköy that I had my first piece of chewing gum.

After disembarking from the Marmaray train, which connects settlements on the coast of the Sea of Marmara, we enjoyed the best cheese börek we have eaten since arriving in Turkey. Then, despite constant rain, we walked along Istasyon Caddesi, admiring the many houses with decorative timber cladding that line the avenue.

We made a small detour to look at a Syriac Christian Church, which looked recently built. We could not enter because a service was in progress. Thence, we walked to the rainswept seafront, where we looked around a museum dedicated to the life of Ataturk. It was housed in a mansion once owned by Greeks. The ground floor is dedicated to the first decade of the Turkish Republic, which was founded in October 1923. The first floor has a display of ethnographic exhibits from Turkey. The second floor is a collection of photographs, items, and books relating to the life of Ataturk.

Next, we came across a Greek Orthodox church. We could enter its covered porch in which candles were flickering. Through the windows of the porch we could see enough of the church’s interior to realise it is quite beautiful. Unfortunately, the church was locked.

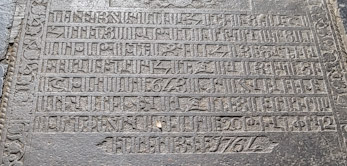

Nearby, we found the huge Latin Catholic Church, which was open. Its interior was nothing special, apart from one religious painting which contained words in the Ottoman Turkish script. The size of the church suggests that there might once have been a large Roman Catholic community in Yesilköy.

Yet another church is a few yards away from the Latin church. It is an Armenian church, enclosed in a compound surrounded by high walls. The entrance was open, and after looking at the church, we joined the congregation (at least 40 people), who invited us to have tea and cakes. A couple of gentlemen began speaking with us in English. They told us that the Çinar Hotel was no longer in business, but it was still standing. They also told us that they are in the textile business. They are waiting for Indian visas because they are planning to visit Bangalore and Tiripur soon because they are looking to buy textile machinery there.

Several people told us that the Çinar Hotel is about a mile from the centre of Yesilköy. As it was cold and raining we decided against looking for it. Despite not revisiting the place I first stayed in Turkey more than 60 years ago, we saw Yesilköy and some of its fascinating sights. It is close to the railway tracks and not on most tourists’ beaten tracks.