THE NATIONAL TRUST looks after a house in Oxfordshire, which was once owned by William Morris. When I came across this property, Nuffield Place, I was surprised, because I believed that the artist and socialist William Morris (1834-1896) had lived in properties in Hammersmith, Walthamstow, Bexleyheath, and Gloucestershire, but not in Oxfordshire.

Nuffield Place was the home of another William Morris, who became Baron Nuffield in 1934, and later in 1938, Viscount Nuffield. He lived from 1877 until 1963. At the age of 15, he set up his own bicycle repair business. By 1901, he had a bicycle repair and sales shop on the High Street in Oxford. Two years later, he was manufacturing motorcycles. In 1903, he married Elizabeth Anstey (1884-1959), a seamstress whom he met when both were members of a cycling club. They never produced children.

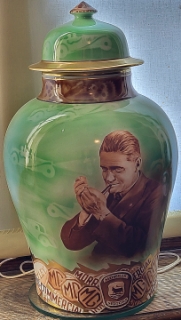

By 1909, he had set up the Morris Garage in Oxford, and was selling and repairing cars. In 1913, he and his small team of workers had built the first car he had designed. By the time the First World War had begun he had acquired larger premises in Cowley on the edge of Oxford. He was already producing cars that were affordable to the popular market, but during the war, his factory switched to producing products needed for the war effort. While doing this, which was not very profitable, he developed much experience in the techniques of mass-production. One of the many models turned out by the Morris factory was the Morris Oxford. This car has made its mark in India because it was the prototype for the Hindustan Ambassador, which was made in India between 1957 and 2014.

After WW1, Morris began making huge numbers of affordable Morris cars, which sold well. William Morris became incredibly rich. However, he was a modest man and extremely generous. He spent most of his money on philanthropy, particularly in the medical field. Many of the institutions he paid for, which bear the Nuffield name, including Oxford’s Nuffield College, still exist. The number of ways in which he helped are far too numerous to be listed. As a child, he wanted to study medicine, but economic circumstances did not allow that to happen. However, because of all he did to promote healthcare and medical research, he was made a Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons in 1948.

Nuffield Place, the house which William Morris purchased in 1933 and lived in for the rest of his life, was built for the shipping magnate Sir John Bowring Wimble, also chairman of an insurance company, in 1914. It was designed by Oswald Partridge Milne (1881-1968), who worked in the office of Edwin Lutyens between 1902 and 1904. When Sir John died in 1927, his widow sold the house, which was then called ‘Merrow Mount’, to Morris in 1933.

The house is spacious and must have been comfortable to live in, but it is remarkably modest to have been the sole residence of a man as wealthy as the automobile manufacturer William Morris. We were shown around it by a knowledgeable lady, who helped us to appreciate how modest were the lives led by William and Elizabeth Morris. Among the many things that interested me was William Morris’s bedroom. In one corner of it, there is what looks like a wardrobe. However, when the doors are open, it can be seen to be filled with tools and a workbench. Morris had his own workshop in his bedroom. His wife continued her seamstress skills, and many chairs were covered with textiles she had worked on. The house contains many books on a variety of subjects including history and politics. One bookshelf is filled with medical treatises. Morris, although he never became a doctor, was interested in reading about medicine.

Nuffield Place contains an iron lung machine, such as was used to help sufferers of poliomyelitis to breathe. On learning that there was a shortage of these machines in Britain, Morris used his factories to produce many of them to distribute to hospitals that needed them. The model he helped design, and his factories manufactured, has some curious details. The handles that were used to adjust the apparatus look just like car door handles. And some other components on the iron lung look very much like the hinges of car doors. These iron lungs were a valuable contribution to the treatment of diseases such as polio.

I could describe much more of what we saw at Nuffield Place, but it would be better if you visit the it. Lovers of gardens will also enjoy visiting this house owned by a William Morris, who did not design flowery wallpapers.